BUT FIRST, A STORY

My Babcia was tough as nails. I used to joke that she could make any plant grow by simply being disappointed in it. She’d tsk at a wilting tomato plant and, the next day, it was in full bloom. I assume you have to be that way in order to survive being forcibly removed from your ancestral village in the Carpathian Mountains, being carted via a freight train to a place you don’t know, and then making the decision to take your family and move (yet again, but this time by choice) to the United States.

The family that I still have in Ukraine isn’t family I know particularly well. They’re my mom’s cousins. They’re my Babcia and Dido’s extended family. I don’t know them, but I’m sure that they have the same moon-shaped Eastern European face that I do. Whenever I’m in a room with other Lemko people, you can tell we’re cut from the same cloth. Round sunflower faces, turned towards the sun.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, some folks asked me where they should donate. Truthfully, I had no idea. It’s hard to push back against the wave of misinformation & propaganda machines.

But I do have a suggestion, which comes from one of my favorite places on the internet: itch.io. Sure, itch has tons and tons of indie games and is a lush rainforest of creativity and experimentation, but it also regularly fundraises for social justice causes through heavily-discounted game bundles.

Right now, itch has a Bundle for Ukraine, which is on sale through the end of the week, with proceeds going towards the International Medical Corps and Voices of Children. They’re about $500,000 away from their $6 million goal, and you should help them get there. Not only does a donation support the medical needs and mental health of those in Ukraine, but for any donation of $10 or more, you gain access to a bundle of over 900 tabletop and video games.

And, in case that number of games is simply overwhelming to consider, here are some of my favorites from the bundle:

SKATEBIRD

I’m pretty convinced that Skate Bird is the result of an escalating series of dares that started with a pun about Tony Hawk, and you can’t convince me otherwise.

Skatebird is exactly what you think it is: you play as a tiny bird, skateboarding around a room, doing sick tricks. There’s also a button dedicated to screaming. It’s immensely silly and a button-mashers delight, and it’s genuinely some of the most fun my partner and I have had playing a game together.

It also doesn’t hurt that the soundtrack contains bop after bop of chill beats with birdsong samples.

Listen: if you haven’t already run to itch to get the bundle just for this game, then you obviously haven’t heard me: SKATE. BIRD. SKATE BIRD, BAYBEE.

THIRSTY SWORD LESBIANS

Thirsty Sword Lesbians is a tabletop roleplaying game that has just as much flirting as it does adventuring. From the game’s website: “Thirsty Sword Lesbians is a roleplaying game for telling queer stories with friends. If you love angsty disaster lesbians with swords, you have come to the right place.”

Though I haven’t played it myself (to be honest, I might be too shy to play this with friends! I am a good, staunch New Englander who keeps all her feelings locked away in a lil’ box), I do have friend who have enjoyed it immensely! The game mechanics are easy to understand, highly customizable, and provide roadmaps on how to navigate emotional storytelling around a table.

If I ever the gumption together, it’s a game I’d love to run for some flirty pals.

A SHORT HIKE

I wrote about A Short Hike waaaay back in 2019. The player controls a small, bobble-headed anthropomorphic bird, à la Animal Crossing. As this bird-person, you have been dropped off to spend your summer with an aunt, who is a ranger in the local state park. You wake up one morning and are eager to receive an important phone call. But there’s a problem: there’s no reception in the woods. In order to get the call, you’ll have the travel to the top of Hawk Point Peak, only a short hike (heh HEH) away from your aunt’s cabin.

It’s a tiny little present of a game: it reminds the player about the many small joys that come with non-purposeful exploration. It asks you to peek around corners. It invites you to see what’s around the bend. With a charming soundtrack and beautiful pixelated landscapes, it’s a warm breeze under your wings, carrying you safely to the ground from great heights.

CELESTE

There are few games that feel utterly perfect, like there is no excess to be trimmed and where the mechanics tie in perfectly to the story it’s trying to tell. Celeste is one of those rare few.

When I picked it up, I thought I would hate it: it’s a 2D platformer that feels like it doesn’t have a lot of room for mistakes. The player controls Madeline, a young woman trying to prove that she can climb to the top of Mt Celeste all by herself. She has been warned that it’s dangerous, but she wants to charge on regardless to prove that she can escape the self-hating part of herself.

The player navigates Madeline through a series of rooms, full of sharp points and traps. Getting through the room is the puzzle: it’s up to the player to find the right combination of jumps and dashes to get to the other side and progress to the next room. The reason that I didn’t immediately bounce from Celeste, despite its difficulty, is that each room is mercifully short. If you fail, the game respawns Madeline right at the beginning of the room. It’s encouraging: you just need to try again. With another beautiful soundtrack, it’s easy to sink into. Stubbornness wins out.

The story of Celeste is of a young woman learning to deal with her anxiety and self-hatred. Her lesson and the player’s are the same: take a breath, and try again.

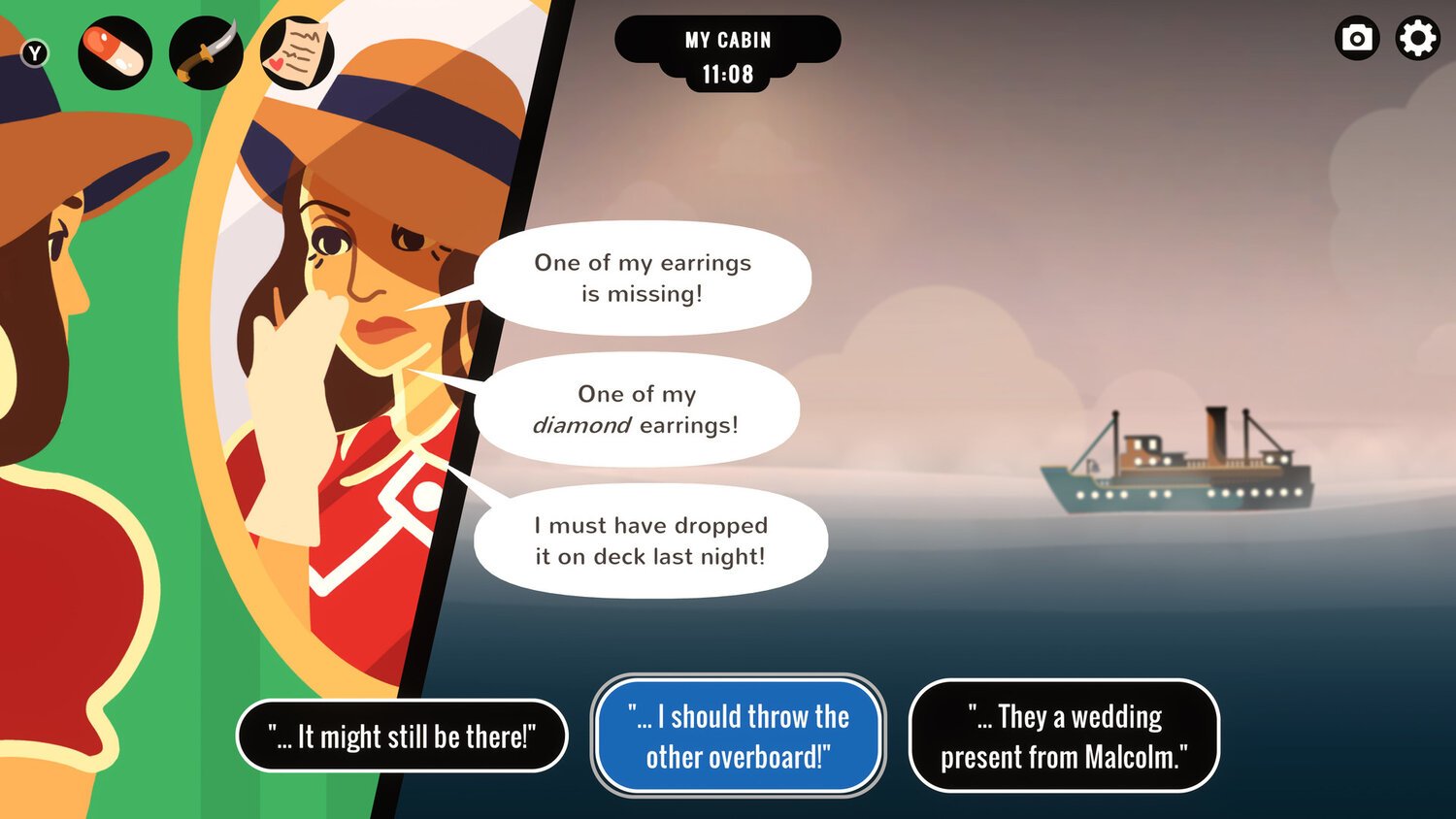

SPEED DATING FOR GHOSTS

There are so many dating simulators. There are dating sims where you can date weapons, or hot monsters, or pugs, or pigeons, or… daddies. Speed Dating for Ghosts is exactly what it sound like: this time, you’re dating ghosts.

The player can choose a room and, within that room, they meet three eligible ghost paramours. Since they’re ghosts, they (of course) have some unfinished business. One is a ghost who is scared of ghosts. One doesn’t know she’s a ghost. One’s name is SPOOKY PETER. Jaiden Animations has a whole video where she and Spooky Peter have a great time robbing a bank.

Speed Dating for Ghosts follows the recent indie dating sim trend of being both tongue-in-cheek and deeply interested in self-exploration and existential questions. But even in an oversaturated market of tender-goofy dating sims, it manages to balance both tones in a way that few others have really gotten down, in part because it trusts the player to choose the experience that they want. Would you rather hang out with a goofy jock ghost? Go for it. Want to ponder the nature of what it means to be alive? Have at it! Wanna rob a bank?

Go for it, kiddo. Just don’t forget to bring Spooky Peter.

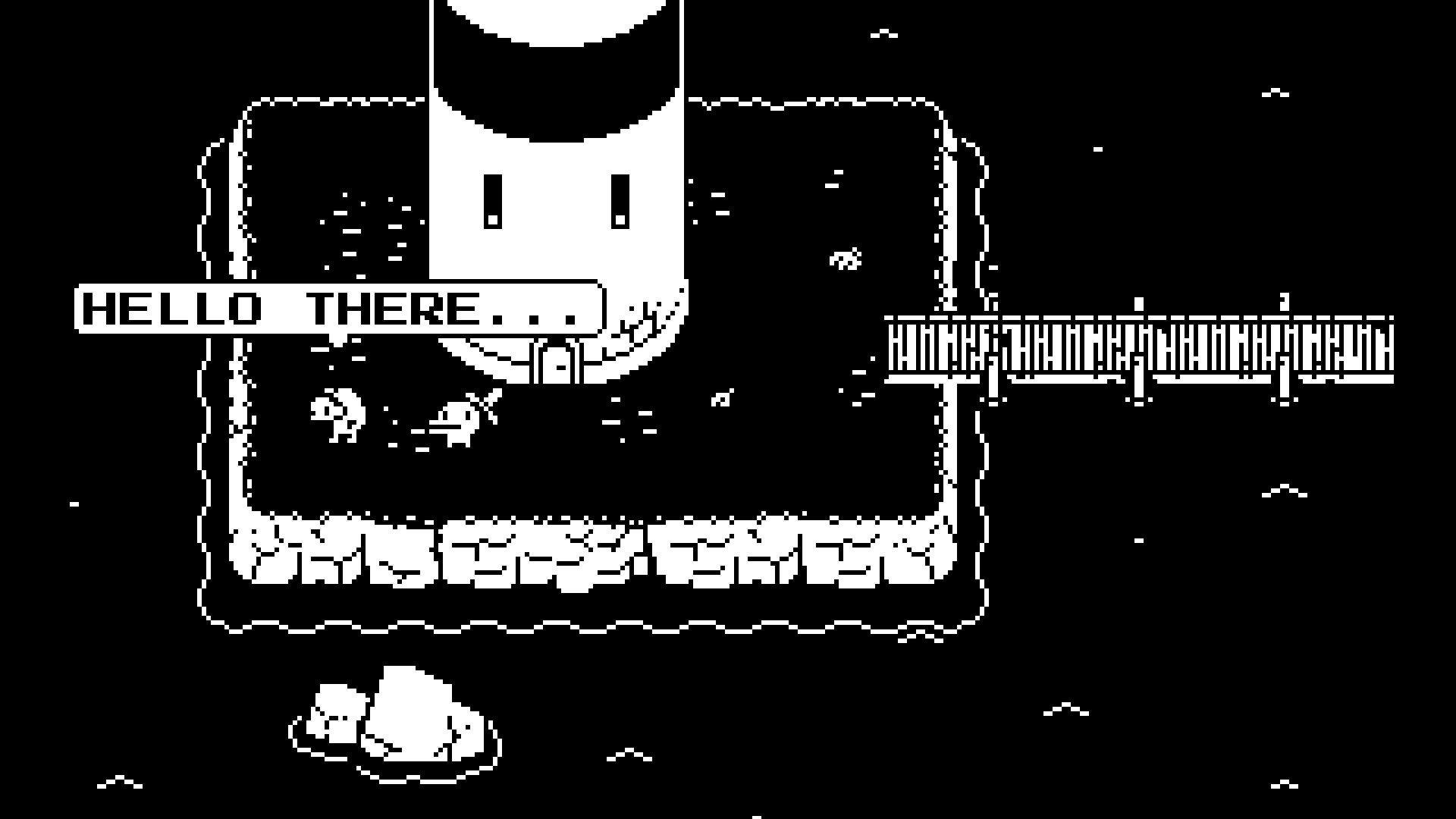

MINIT

Minit’s conceit is simple: there’s a curse on your character that makes each day end after only one minute.

And that’s not “in-game one minute,” that’s “one actual human minute, counted down, over and over, until you beat the game.” It’s a miracle that Minit makes this mechanic feel entirely sustainable over the course of the game. Each loop becomes a task that asks, “What will you do in this one minute?” Will you solve a puzzle? Will you get a sword? Will you talk to that guy who has something to say to you? Each task is entirely completable within the time given to you and, once it’s completed, it opens up possibilities for what you can do in the following minutes.

Despite the stringent-sounding limitation, Minit is an absolute charmer. The time limit is always present, but it never felt unfair. it was just the right amount of pressure to make me want to keep going and find out what the next minute might bring.

BABA IS YOU

Oh, Baba is You. I never actually finished this game, but I loved every minute I spent with it, even when those minutes included some of the sweetest agony my little rule-loving brain could possibly imagine.

Baba is You is a aesthetically bubbly puzzle game that establishes a number of rules for each level, and then asks you to break those rules to get to a win state.

All of these rules are structured like the title. “BABA is YOU” is a rule that means that the player controls a little bunny creature named Baba. Each of these pieces is movable: the player can push BABA or is or YOU while attempting to build new rules. So, if BABA is YOU is the rule, but there’s also the word ROCK in the level, pushing ROCK into the place of BABA makes the new rule ROCK is YOU, and suddenly the player is a rock, moving around the screen.

Something about 1) being told a rule and then 2) having to figure out how to break it in just the right way… absolutely destroyed me, but in a way that I think is good for me. It challenged my internal rigidness around rules, “right,” and “wrong.” Though it wasn’t always the most comfortable place for me to sit, it was immensely valuable and also, more importantly, actually pretty fun.

SUPERHOT

A classic! Superhot is a first-person shooter where time only moves when you do.

Well, that’s not quite right: time still moves, but very, very slowly. Superhot takes a genre I could care less about (first-person shooting) into a highly-stylized and genuinely challenging thing I do love (puzzle games). It’s the bullet time scene from The Matrix amped up to 100 and, when everything goes just right and you’re dodging bullets left and right, you do kind of feel like a bad-ass.

GAMES I HAVEN’T PLAYED, BUT AM EXCITED TO TRY

Kingdom: Two Crowns: I played Kingdom: New Lands some time ago, and I’m excited to play this next iteration of this indie delight! From the game’s website: “Kingdom: Two Crowns is a side-scrolling micro strategy game with a minimalist feel wrapped in a beautiful, modern pixel art aesthetic. Play the role of a monarch atop their steed and recruit loyal subjects, build your kingdom and protect it from the greedy creatures looking to steal your coins and crown.” Resource management, city building, and beautiful art? Yes. Yes yes yes.

Quadrilateral Cowboy: This is one of those games that I’ve been meaning to play for YEARS, and yet I never have. I just think the conceit is so interesting: “Quadrilateral Cowboy is a single-player adventure in a cyberpunk world. Tread lightly through security systems with your hacking deck and grey-market equipment. With top-of-the-line hardware like this, it means just one thing: you answer only to the highest bidder.” It’s a game where the puzzles are coding!

Literally everything on this Kotaku list, but especially Ynglet, which has the chill puzzle vibes that (by now should be readily apparent) I crave.