PAPERS, PLEASE

March 8 was International Women's Day. I went to the San Francisco Gender Strike, a feminist march against US Immigration and Customs Enforcement ("ICE"). Speakers went up, one by one, each with their own personal way of encouraging our community to take a stand against mass deportation, xenophobia, and policies that threaten and affect members of our community. One speaker came up and, in the middle of their speech, directly challenged law enforcement, ICE agents, congresspeople, etc. to stop following orders. It was a clear directive: stop enforcing policies that are hurting real people.

It seemed such a simple thing when it was stated like that.

It's easy to imagine what I would do if I were one of the people being addressed by that plea: I imagine myself standing up to some boss, quietly stating, "No, absolutely not. This policy is wrong." I imagine the accompanying swell of music & the shift into a more technicolor world. I imagine the resulting biopic where I am played by some Hollywood up-and-comer hoping for an Oscar nomination.

So simple.

But I've played Papers, Please, a 2013 "dystopian document thriller" game put out by Lucas Pope, and I'm afraid that I know something a little darker about myself: how easy it is for me (and you, and all of us) to follow rules. And how that choice isn't extraordinary or even intentionally malicious, it's the most mundane thing in the world.

desk job

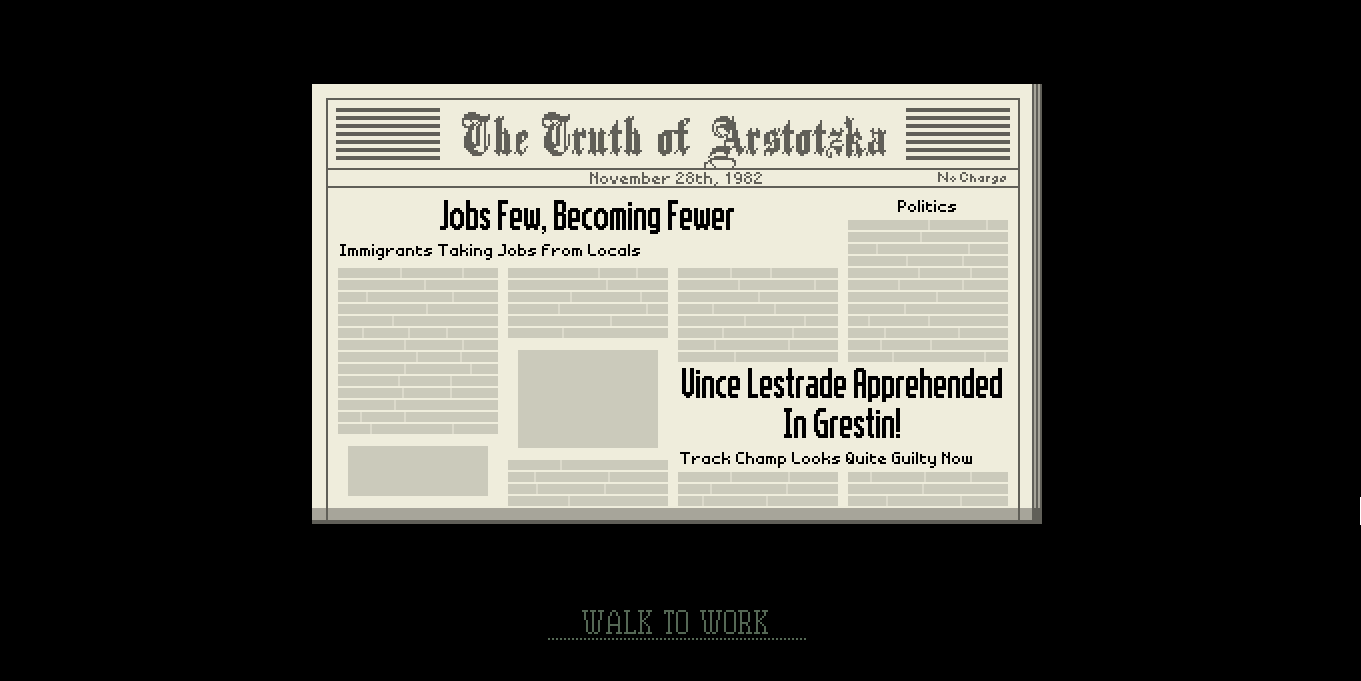

.Papers Please casts the player as a nameless border officer in the fictional Eastern-Bloc-y country of Arstotzka in the mid-1980s. Tensions with surrounding countries are high, and the border has only just been reopened after a long war with Arstotzka's neighbor, Kolechia. The player's character has a family, for whom they need to make enough money every day to provide housing, food, and heat.

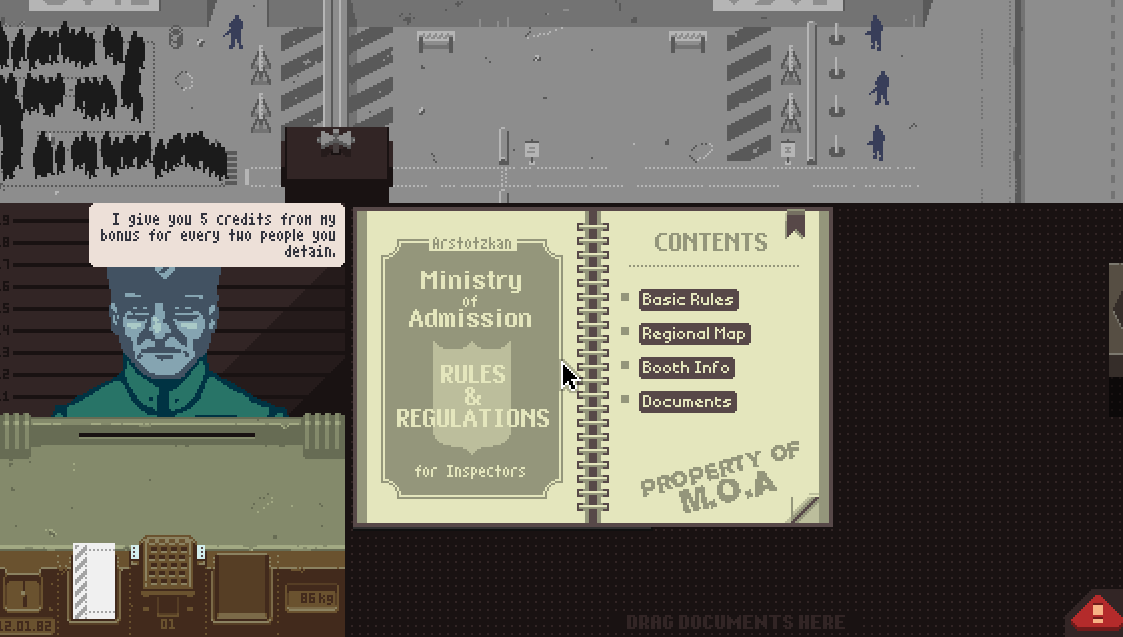

Your entire job (and the entire game) is this: decide who can come into the country, and who can't, according to their documents. You look for inconsistencies: misspelled issuing cities; wrong dates of birth; mismatching photos. This is how you figure out if someone comes in or is turned away.

There is only one location in Papers, Please: the office in which the player's character works. Pixelated guards patrol outside. A pixelated mass huddles in a line. Your pixelated office (crammed in about 3/4 of the screen, and never having enough desk space to see all the documents you need to evaluate at once) stands waiting.

A pixelated clock counts down in the corner of the office, altering you to the fact that you have only so much time to process as many people as you can: your ability to assess documents quickly and correctly determines how much you get paid at the end of the day. If you process too many folks incorrectly, your pay gets docked.

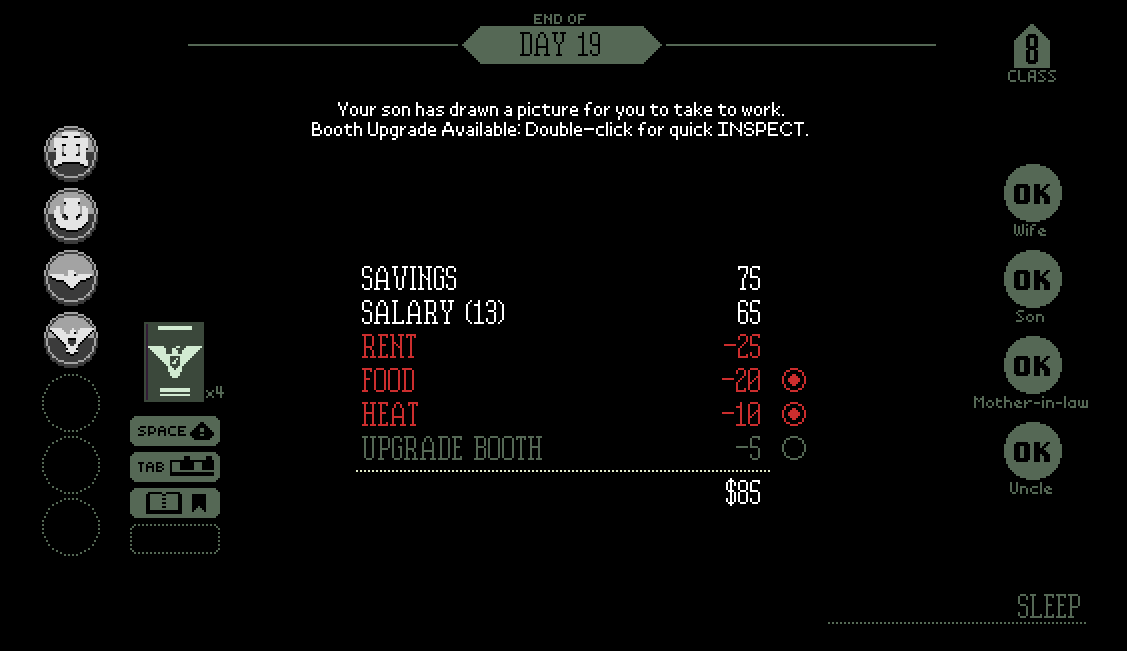

That pay is what will keep your family fed, warm, and healthy. (As a note: you never see this family in the game; they are represented by a screen at the end of each day that tells you how much money you made, how much pay was docked, and how your family is doing. It's cold and clinical, but deeply efficient.)

Rule Follower

So, it is clear from the start of the game that, in order to survive, you have to follow the rules. You can't leave your job. You can't leave your country. You just process people--day in, day out--and hope that you do well enough to feed your family and keep them well. Not to mention your son wants a new crayon set, and that shit's expensive.

Complicating matters is that fact that, every day, the player is greeted with a new set of rules.

The game starts off simply: reject anyone unless they carry an Arstotzkian passport. Easy. I can get through 17 folks if I really get rolling. I don't even think about those pixelated faces that come in, and I don't think about the text that expresses their disappointment if I turn them away.

But the next day, suddenly I am told that I can admit immigrants, but they need valid entry permits. And the next day, after a terrorist attack (from a native or an immigrant? Who knows? The paper claimed they were from Kolechia, but I suspect otherwise), I am told that they need an ID supplement. And then there are the body scans. And then there are the vaccination forms.

My desk soon can't even fit all of the documents and the rule book at once.

Truth be told, I'm pretty good at this: I like looking at data. I breeze through the first few days, saving up a bit of money until I feel downright comfortable. But after a bit, my eyes get tired. As the rules pile up, it becomes much easier to make mistakes. Suddenly, money is tighter, and I can't afford to make mistakes anymore. When I'm desperate for money, following the rules is my job.

Morality vs mundanity

If the money stress wasn't enough, as the game continues, I find myself not just processing documents, but assessing the moral ambiguities that are carried into my office by the people trying to pass through:

There's the woman whose husband came through the checkpoint just before her. His papers were in order. Hers were not. But she begs me to let her through, even through she has no bribe to offset the potential penalty I'll face for ignoring her lack of paperwork.

There's the border officer who gives me a cut of his earnings, depending on the number of people I detain at the checkpoint. I could just turn those people away once I see that their paperwork is forged, rather than handing them over to the officers... but turning them away doesn't get me money.

There's Jorji, who keeps coming to my checkpoint, despite never having the right papers. ("Cobrastan isn't a real country," my avatar tells him as I hand him back his clearly forged passport, written in crayon. "Oh, OK," he says.) I look forward to his visits, even when it becomes apparent that he is smuggling drugs across the border. ("You have tough job," he says as detain him, "I rather sell drugs!")

There are the Arstotzkian passports I confiscate because, if I don't, I'll get penalized.

There are the Obristani passports I illegally confiscate because, if I don't, my family won't be able to escape Arstotzka.

There are the times I let people slide on through, because I have some money tucked away (from the people I detained), and there are the times I just do. my. job., because I can't afford to to otherwise.

For a game with one screen and one clear directive, I found myself talking about my role in the game in the first person. ("I turned them away. I had to.")

And for a game that takes place in a Soviet-inspired country, it was clear to feel the broad, desperate grasp of capitalism. I was going to do everything to protect my small pile of stuff, and would stomp on anyone who threatened me & mine.

breaking the rules of a system you can't leave

Right here, in 2017, I find myself in a world where the US government passes down orders and expects folks to execute those orders exactly as they are stated. It's always been that way, but it somehow feels more that way these days. A quick Google search reveals that folks are noticing the connection between Papers, Please and current news stories about immigration.

More than anything I've played, Papers, Please made me truly a little disgusted with myself. Sure: the game provided no other out (unlike the world outside my computer), but it was a little reminder of the times I've stayed silent or followed the rules to keep myself "safe."

I think it's easy to think about "what we need to stand up to" as a clear, definable thing. I think it's even easier to think that there will be one moment when it's clear that we need to fight back. We forget that the horror lies in the mundanity of evil. We can be the perpetrators of great harm and hardship not because we believe in those things, but because of the boring, rote, and (again) mundane system that we find ourselves in.

I find myself endlessly wrestling with the question of how to break the rules when you can't leave the game. But, what I ultimately come back to is Ursula K Le Guin's quote from her speech at the 2014 National Book Awards:

We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable – but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art.

There are no "good endings" in Papers, Please. There are some endings that are better than others, but that doesn't make any of them "good." Nor would I call Papers, Please a fun game. It was described in a Polygon review as "a dirge." But that doesn't make it worthless: Polygon also called it "a meaningful experience in misery."

A memory of burning yourself keeps you from touching a hot object. Maybe this game serves a similar purpose. Maybe its one-step-removal from reality allows us to see things more clearly, to assess our own weaknesses so that we can become stronger, to better understand our world for what it really is.

All I know is that I've played this game a couple of times since it came out in 2013, and when I played it last night, I cried. I was horrified. I saw things more clearly.

Resistance and change often begin in art.