Kentucky Route Zero

Anyone who has known me for any length of time has probably heard me proselytize about Kentucky Route Zero, an episodic point-and-click "adventure," put out by Cardboard Computer.

It's a game in five acts. Although only four acts have been released so far, even if act V never comes, I'll continue to hold it up as a stunning example of how much innovation can occur with even the simplest mechanics and most familiar stories.

It's really very simple.

Kentucky Route Zero opens with Conway, a man who is making his last delivery of antiques for his friend (former girlfriend? aging peer? boss?) Lysette. There's only one problem: the address he's supposed to deliver to doesn't exist, or it does, or it does but it's on the other side of The Zero, a route Conway is encouraged and/or discouraged from taking. The Zero (which is always styled with italicized, radio-static font) is a road that no one seems to know exactly how to access, except for someone's sister who disappeared yet is definitely a ghost in the wires. But that's a story for later.

In fact, I'm not going to get into the plot much at all in this review. Not because it's not important, but because I feel that the story is best experienced first-hand.

However, I will say that I found it to be a beautiful and heartbreaking story about debt in all its forms, and about hauntings. I will say that it is magical-realist Americana. I will say that I was not in the least disappointed. I will say that.

The game mechanics are simple as well.

Kentucky Route Zero is, at its core, a Point-and-Click adventure. However, there are no puzzles to solve, no solutions to find. Literally the only thing you do as a player is occasionally ask a character to walk around an area, or to talk to folks, or to decide how you speak with other characters.

It's a short game, with each act ranging from a play-through of about an hour to a few.

You switch from character to character according to the whims of the developers: you have no choice in who you control at what time. Sometimes you're Conway. Just as likely, you're someone else, so that it becomes abundantly clear as the game continues that you can count on no one character to be the central "protagonist" of the game.

Most strikingly, what you choose to say to other characters has no affect on the game's outcome. Your choices don't change what happens to the characters down the line. it doesn't change the ending... at least through what has currently been released.

However, what surely started out as a necessity born from trying to develop a game within a very small team ends up being a recipe for creating something that is wholly different from anything I've ever played: Your choices don't shape the future, but they absolutely shape the past.

Kentucky ROute Zero is a story told in reverse, even as the characters move forward in time.

For example, in the above photo, Conway sits at a table with Lysette, having a conversation.

Above, the choice the player is given is NOT to intuit what Lysette is saying, BUT INSTEAD to intuit what Conway thinks Lysette is saying. The game's dialogue is ultimately meaningless in terms of game mechanics, as it has no influence on the terminal path. However, this dialogue mechanic is deeply meaningful in creating a bond between characters. More than that, it creates a bond between the player and the characters. Suddenly, the player is asked to create and participate in the past relationship between Lysette and Conway.

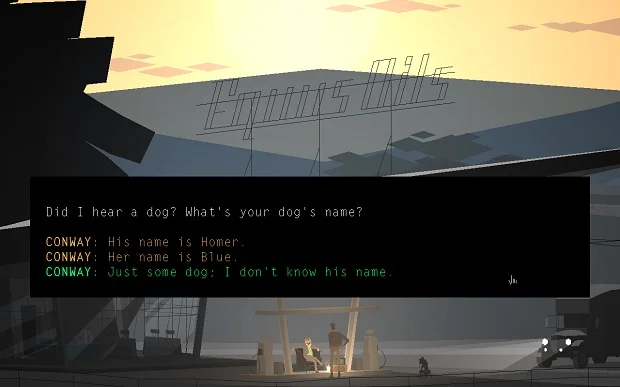

For an example of how effective Kentucky Route Zero is at this, I would like to quickly refer to a 2013 interview between Rock, Paper, Shotgun and KRZ co-creator, Jake Elliott, where the interviewer references one of the first moments in the game, where you choose what to name the old hound dog that follows Conway around:

RPS: So I really liked interacting with the dog, Blue. I’ve decided that is her name, because that’s the choice I made, and the other choices are wrong.

Jake Elliott: I’m feeling good about the way that people are responding to that. It was a really late addition, actually. We just added it as a detail, and it started to seem like a really compelling element in the game. I’m glad you felt attached [laughs].

The way the question is introduced by the interviewer betrays the effectiveness of Kentucky Route Zero: not only does the interviewer have to correct himself ("oh, right, other people can name the dog other things"), but he also jokingly adds that "the other choices are wrong."

When you're given the option to name this dog (with your choices being "Blue," "Homer," and to leave the dog nameless), it feels different from the Pokemon-style "name this critter anything you want." By only giving me only three choices, I had to focus more on the "why" behind each choice. Was Conway a fan of The Odyssey? Was he a simple man with a simple name for his simple dog? Was he like my grandfather, a man who always had animals but named not a single one of them?

Just like the conversation with Lysette, I wasn't asked to make a decision that would affect where I'd go in the game, or what'd I'd see. I was simply creating the history of Conway and his dog,

his dog who was clearly named Blue, because all other choices were wrong.

(As a note, there's another Rock, Paper, Shotgun article that talks more about KRZ's "backwards" story-telling. I recommend it.)

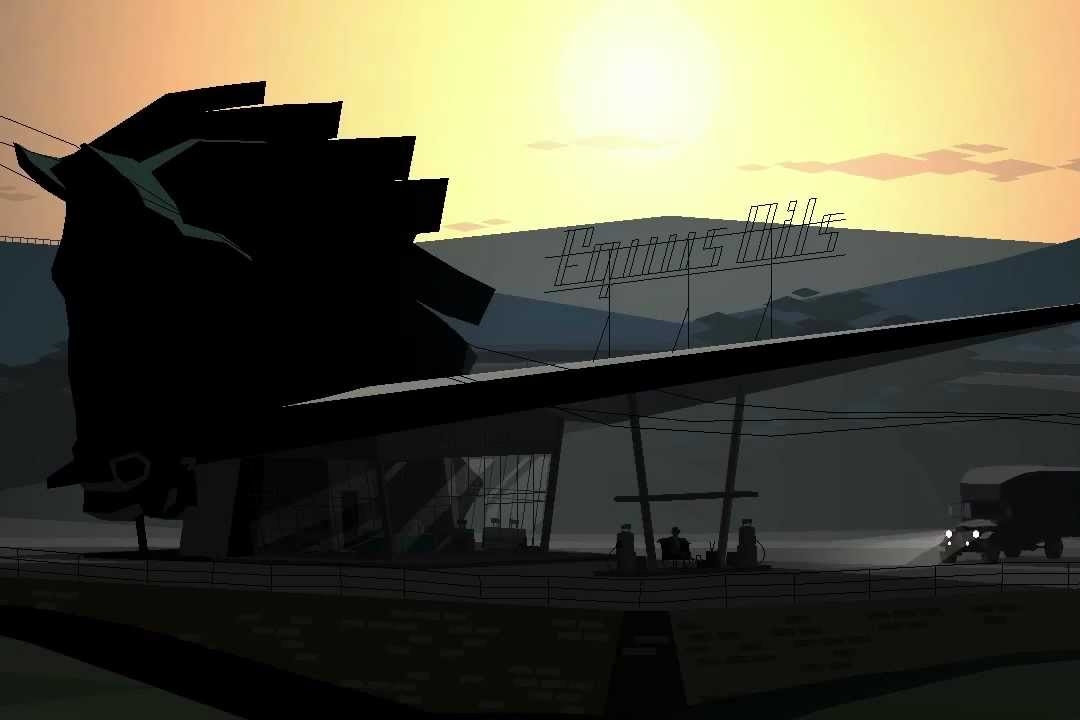

Kentucky Route Zero is also a sight for sore eyes.

From its opening moments, Kentucky Route Zero is a beautiful game. I fell deeply in love with the colors and style. Living in the Bay Area, I pine for East Coast deep summer nights, for the haze you get on days that are just too hot, for the colors of the East Coast mountains and valleys. Sure, the sky out West is big and beautiful, but it's just not the same.

Kentucky Route Zero's creators have referenced their study of scenography (the study and development of stage pictures in the theatre) and how they were particularly influenced by Pamela Howard's 2001 book What is Scenography?

Kentucky Route Zero co-creator Tamas Kemenczy even gave a speech about it at GDC:

You can feel their study of scenic design and theatre when playing the game. There is an appreciation for space and, more than that, for spaciousness. Even playing the game on my dinky laptop, it felt vast and grand. Scenes literally unfold. The camera pulls away.

At one moment in the game, I had the characters pull off the road just to look at the view. I decided to wait and stay, to enjoy the deep blue hills. I waited there for a solid minute, lulled by the crickets and the wind, until a large meteor flashed across the screen.

It was like in seventh grade chemistry, when we were given phosphor, and how that one kid lit it on fire (even though we were told not to), and how the room was suddenly blinding and we all laughed in surprise. It was just like that.

The music is gorgeous, too.

The soundtrack is by Ben Babbitt and stretches from drone electronica to Christian gospel revival. One song in the game sounds like it was sung by a woman. In a later interview, Babbitt explained that it's actually his voice, manipulated until he was performing "vocal drag." The result is keening and haunting.

I sometimes listen to the soundtrack on public transit. I commend Babbitt for making music that makes riding the bus feel like a relaxing and humanizing activity.

Like i said, I could talk forever about Kentucky Route Zero.

I've cornered people at parties, have gone on diversions at work, have literally begged my partner to play the first ten minutes. (He politely declined and went back to Pokémon.)

There's more I want to say here: I want to talk about Ezra and his brother, the eagle Julian; or I want to talk about the ghosts in the mines; or I want to talk about ironside ship populated entirely by cats; or I want to talk about the part of the game that was told through CCTV cameras and where a cat followed the characters out of the building and hung around for the rest of the game.

More than anything else, I want to talk about how Kentucky Route Zero takes a very familiar medium (the text adventure/the Point-and-Click/heck: the video game) and asks, "OK, but what else can I do with this?" Every line is blurred. Every button is pushed. It is a game that, given its mechanical and programming limitations, instead found room to experiment in other aspects of game design. Because of this, the moments of connection between the game and the player are both exquisitely planned and, yet, feel completely surprising.

As an example, I'll end with this:

Since it's made by a small team, the acts of Kentucky Route Zero take a while to come out: it was about a year and a half between the release of Act III and Act IV (and there were plenty of angry remarks on Steam). Like other delayed developers (::cough::Infinite Fall::cough::) to sate people's thirst, the KRZ team puts out little interstitials between acts.

Between Act I and Act II was "Limits and Demonstrations," a digital retrospective of one of the character's artwork.

Between Act II and Act III was "The Entertainment," a VR-compatible staging of a play written by one of the characters, with the player in the role of a nameless, lines-less, actor (who is very much based on Beckett's silent protagonists in "Act Without Words I" and "Act Without Words II").

Between Act III and Act IV was "Here And There Along the Echo," an actual phone line where you could call in and listen to the history of the fictional Echo River that runs along The Zero. When you called in, you got into a phone tree that directed you to press buttons according to your needs. (Were you holding a snake and didn't know what to do next? Press _. Did you want to learn about the subterranean sounds of The Echo? Press _. &c.)

I called in. (Of course I did.) On one of my calls, the recording asked me to give one of my early memories after the sound of a tone. And I did.

Later, when Act IV came out, there was a moment where a handful of the characters were at a phone booth on The Echo. And, lo and behold, when one of the characters goes to the phone to check their messages, there on the other end of the line were voices of actual human people who called in to "Here And There Along the Echo" and left their memories.

My heart skipped a beat. First, the game has no voice acting; dialogue is text only. So, it was the first time in the game that I clearly could hear a person's voice, outside of a song. Second, I was suddenly, improbably, hearing the voices of people who had also called in to "Here and There Along the Echo." People just like me. It was a clear, shining line between the outside world and the inner world of the game.

And it was beautiful. Sure, both within the game and without, we weren't sure what agency we had in affecting the future, but we had all made the decision to call in and, for a moment, we all had decided on a shared past.