GHOST BUILDINGS: Sarah Winchester, Ghost Stories, And The SIms

This essay was originally given as a talk for PLACE TALKS on September 19, 2019

In the Northeast, where I grew up, we had no shortage of ghosts. In fact, the town seemed to create new ones every year. We had an annual walk on Halloween, called “The Ghosts of Ridgefield,” where our soccer coaches and moms of friends would put on period clothes and hide in the older houses on main street. We’d walk by and they’d pop out for the most apologetic of scares, before launching into the storied Colonial history of the town.

I very much believed in hauntings as a child. My close friend and I told everyone we could see ghosts, and had a brief period of atypical popularity when we went into fake trances in the school lunchroom.

This same friend lived down the street from me. Her family gave me a funny feeling, and my mom only let me go over once. Years later, my partner’s parents bought that house, and he told me that when he brought an empathic friend over, she balked on the doorstep, taken by a sudden chill.

A Woman, Haunted

When I read that intro to my partner, he said that he had never said it, that I must have made it up. When I swore that he had, he responded, “I think I would remember something that fits so perfectly.” I’m still going to tell that story, even knowing it’s untrue, because it has such a great arc to it. The ghost-loving friend. The ghost-filled house. Shirley Jackson would have a field day.

It’s the same feeling of kismet that one might feel at the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose.

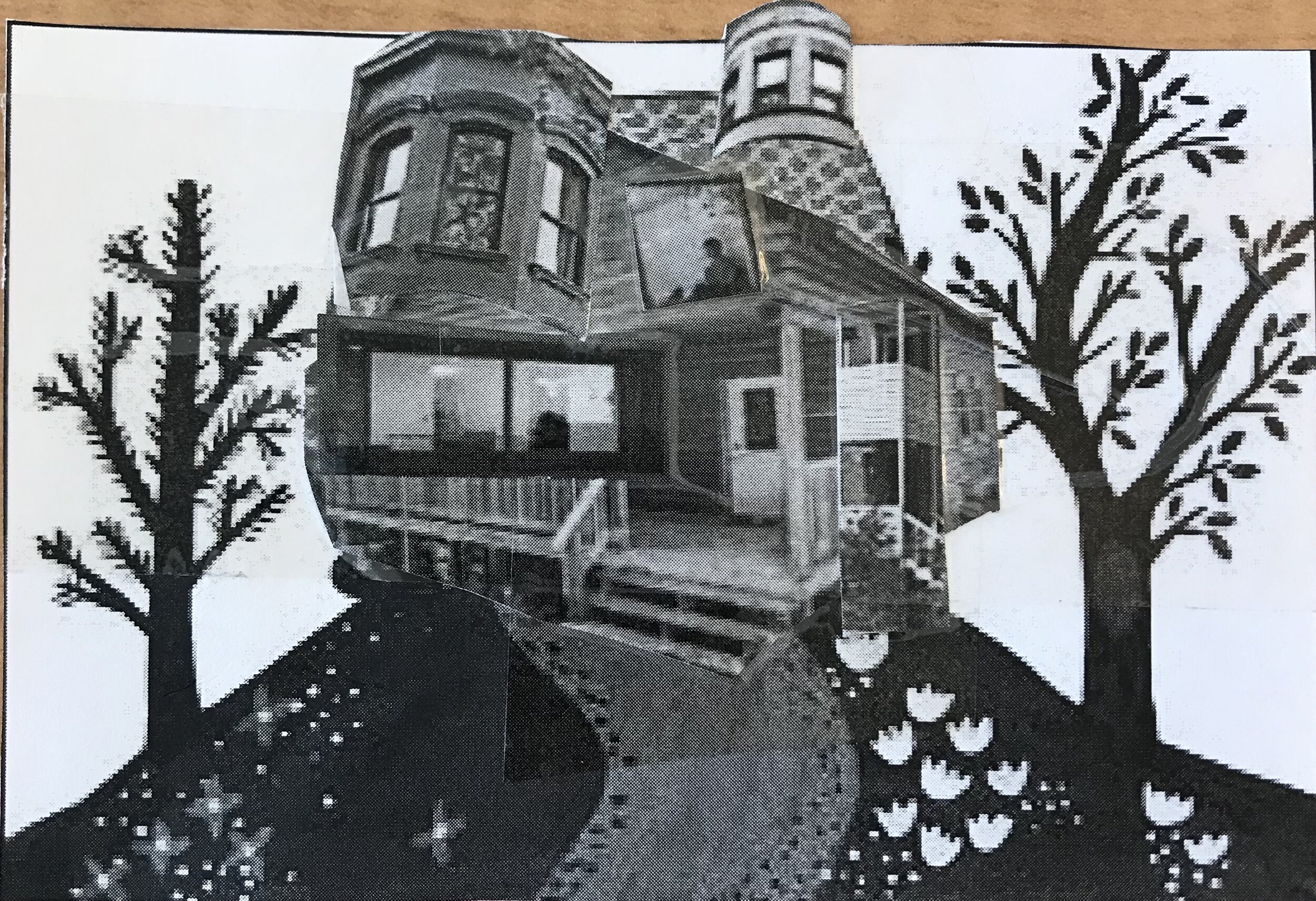

To call the Winchester House “odd-looking” would be an understatement. It’s a non-symmetrical mishmash of odd-angles annexes, some too small, some too big. Rooms connect via narrow and non-intuitive passages. It’s easy to get confused about where you are, and where you’ve already been. Today, visitors are shown a number of odd attractions, like the “staircase to nowhere,” where, rather than meeting a landing, the top of the stairs ends at the ceiling.

A giant building, four stories tall with over 160 rooms, it’s marketed as the physical embodiment of its former owners’ compulsions.

That owner was Sarah Winchester. It’s said that Sarah was haunted by ghosts. Not the ghosts of the many family members who died prior to her leaving her Connecticut home and moving west -- her infant daughter, her mother, her father-in-law, her husband -- but haunted by the tortured souls of all those who were killed by the Winchester repeating rifle, the gun that was said to have “won the west,” used by the likes of Wild Bill Hickok and Annie Oakley in their traveling shows, and to which Sarah could attribute her fortune, having married into the family.

After the death of her husband, Sarah allegedly went to a medium, who told her that she would be haunted by the spirits of those murdered by Winchester guns, unless she built a giant home to confuse them. Rumors swirled that Sarah was compelled to keep her builders working, night and day, in neverending supplication.

Inspired to look into the story of this haunted woman, author Mary Jo Ignoffo published Captive of the Labyrinth in 2010, the first (and only) comprehensive biography of Sarah Winchester. Ignoffo found evidence of Sarah’s alleged madness to be… lacking.

In the corner of “no evidence,” Ignoffo included that the name of Sarah’s alleged instigating medium -- Adam Coons -- can’t be found in any business records; that Sarah hardly kept her staff working ‘round the clock, but released her construction teams for months at a time, once writing that she did so to “take such rest as I might”; that she wasn’t even a full-time resident of the San Jose house in the later years of her life but mainly resided in an aggressively normal-looking home in Atherton, CA; that the famous staircase to nowhere and its architectural twin, the door to nowhere are results of damage from the 1906 earthquake, after which Sarah carted away the rubble and closed off damaged sections of the house, refusing to rebuild areas she now saw as structurally unsafe. These latter changes allegedly led even Sarah to say to a friend that the house looked “as though it had been built by a crazy person.”

What Ignoffo does find evidence for is that Winchester was very wealthy, and very excited about architecture. Sarah had hired, and fired, two architects, preferring to do the planning herself. Correspondence with family reveals a certain “aw shucks” casualness. In a letter to her sister-in-law, Sarah wrote, “My upper hall which leads to the sleeping apartment was rendered so unexpectedly dark by a little addition that after a number of people had missed their footing on the stairs I decided that safety demanded something to be done so, over a year ago, I took out a wall and put in a skylight.”

Sarah made no effort to explain herself to the general public -- why would she? This house was for her, not for them -- so the general public was left to create their own stories about this wealthy, reclusive widow and her growing house.

Ignoffo notes that Sarah built her San Jose house at the rise of yellow journalism, where, due to increased competition, newspapers published embellished or sensationalist stories in order to draw readers to their pages. Local papers speculated about Sarah’s motives, and each new article added a twist to the story. To quote Ignoffo, “First and foremost, papers identified her as superstitious. Added to that, in order, were claims that she was a snob, she was afraid of death, [...] she was a spiritualist, and, following the 1906 earthquake, she was mad.”

We loved a good ghost story then. And we love a good ghost story now. Especially when it stars Helen Mirren.

When Sarah Winchester died in 1922, her properties were put on the market, including the San Jose house. At its auction, given its size and impracticality as a living space, no one bid to buy it. Instead, a man named John H. Brown offered to lease the property, with the option to buy later.

This wasn’t Brown’s first property; he had previously built an amusement park in Canada, called the Crystal Beach Resort, where, in 1910, a 10-mile-an-hour roller coaster Brown invented had thrown a woman to her death. When Brown moved his family to California, he saw an opportunity in the Winchester house.

At this point in history, America had manifested its destiny, and the “‘gun that won the west” had played a large role in this land-grab. Now that colonizers had established themselves on the West coast, a new anxiety arose. Ignoffo wrote, “The image of wandering souls of brutally killed cowboys and American Indians at the hands of settlers with repeaters provided lurid fodder for an already substantial hyperbole.” As someone who directly gained from the Winchester repeating rifle’s popularity, the weirdness of Sarah’s house could be read as an external representation of internal guilt-fed turmoil. She could be the repository for regret, an icon made to bear our sins so we could continue on, lighter-hearted.

(As an aside, when I visited the Winchester House, the gun props for the tourist photo were replaced with a giant key. You know: to “unlock the mysteries of the house.” However, while waiting in the courtyard for your tour to start, you can still play a shooting gallery carnival game, if you’re so inclined.)

After leasing the property, the Browns opened the house just six months after Sarah died, and had no qualms with leaning into its architectural horror.

The Winchester Mystery House, now a trademarked name, updated their “History” page in 2017. Prior to the update, their statements had an air of implied fact about Sarah’s designs. My favorite one is in regards to why there are so many electric lights in the house, an expensive amenity at the time. The about page explained: “Supposedly spirits feel conspicuous and humiliated by shadows, since they cannot cast their own.”

Perhaps because of recent articles about Sarah Winchester and the lack of ghostly evidence, the “about” page now has open-ended rhetorical questions like, “Was she haunted by the ghosts of those felled by the ‘gun that won the west’?” which allow that the answer might be “no” while heavily implying that it’s actually “yes.”

Nonetheless, if you go to the Winchester Mystery House this fall, you can see their new immersive theatrical experience. Titled “Unhinged,” it invites patrons to “trespass into forbidden rooms of the house—never before seen by the public—confront malicious spirits, and encounter terrifying scenes that will reveal the home’s twisted tales and secrets.

And, like any good theme park, when you exit, you’ll go through the gift shop. You can pick up a DVD of Winchester on the way out.

Ghost of the Home Maker

Even with the mountain of evidence against the popularized story of her “haunting,” the story of ghost-plagued and madness-racked Sarah Winchester sticks.

In Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, author Colin Dickey asserts that ghost stories “give expressions to our unstated desires and fears. They can also, just as easily, mold reality to our preconceived notions and cover over a messy reality in favor of well-worn cliches and urban legends.”

In this case, Sarah Winchester makes a good ghost story, in part, because it’s so familiar to an American audience. The popular belief of Sarah Winchester as haunted, or twisted, or… unhinged… comes from a widespread American assumption that what house looks like is reflective of the interior character of the person keeping it. And, since women are predominantly the ones expected to keep house, this is a particularly gendered belief.

Consider fairy tale witches, crones with houses of aberrant architecture: the witch with the gingerbread house, or Baba Yaga stilted up on chicken legs, both of whom used their houses to lure and kill children in acts of mothering gone horribly wrong.

Or, think of more contemporary movies, especially ones with female characters whose bodies are seen as out of control. There’s What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, with Gilbert’s mom eating on the couch, leaving her house in disrepair. There’s the 2006 children’s animated film, Monster House, where a man marries the “Fat Lady” from a local circus. When she accidentally falls and dies, she possesses the home and eats the local children. Her widower husband says, “She died, but she didn’t leave.”

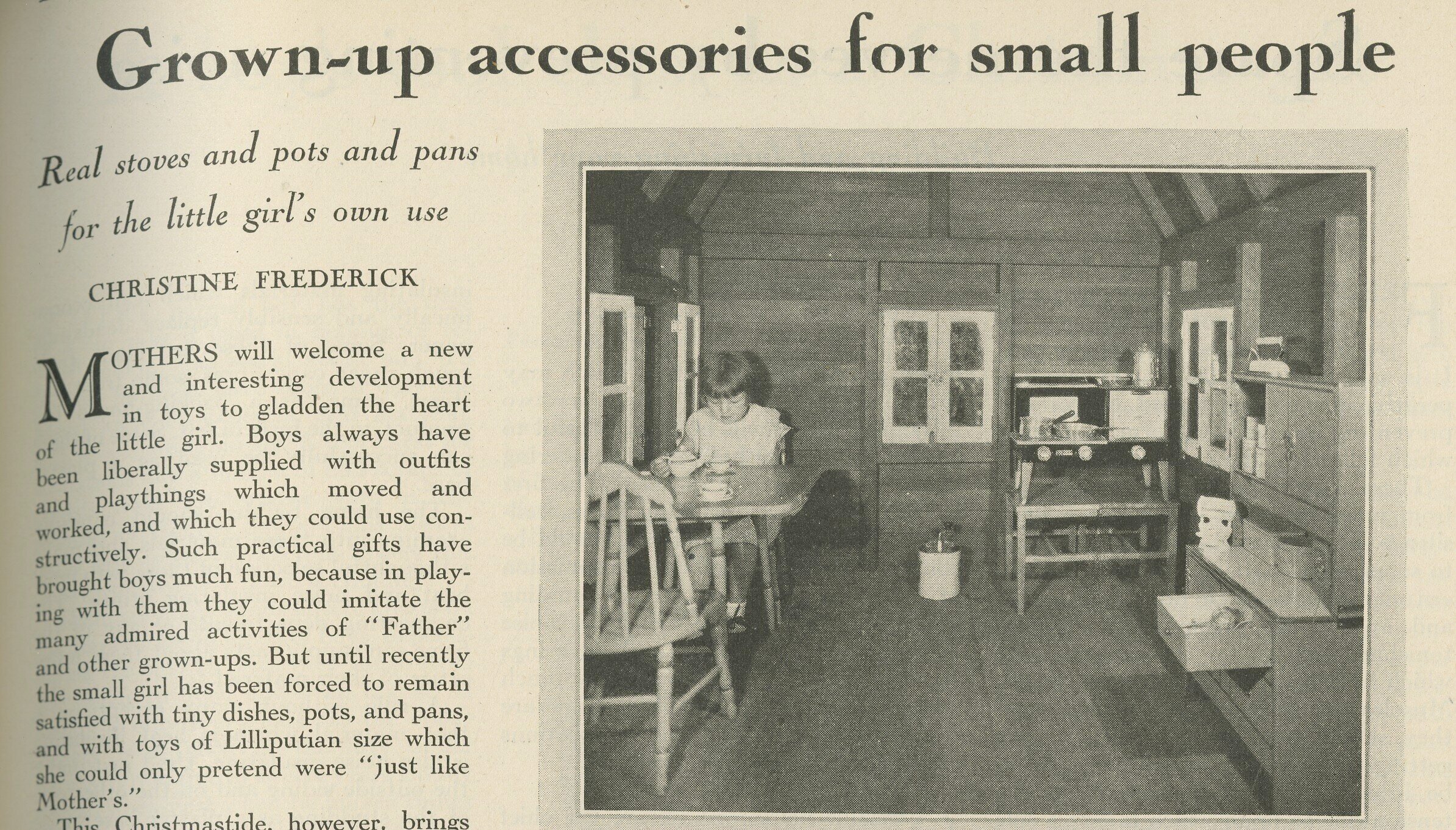

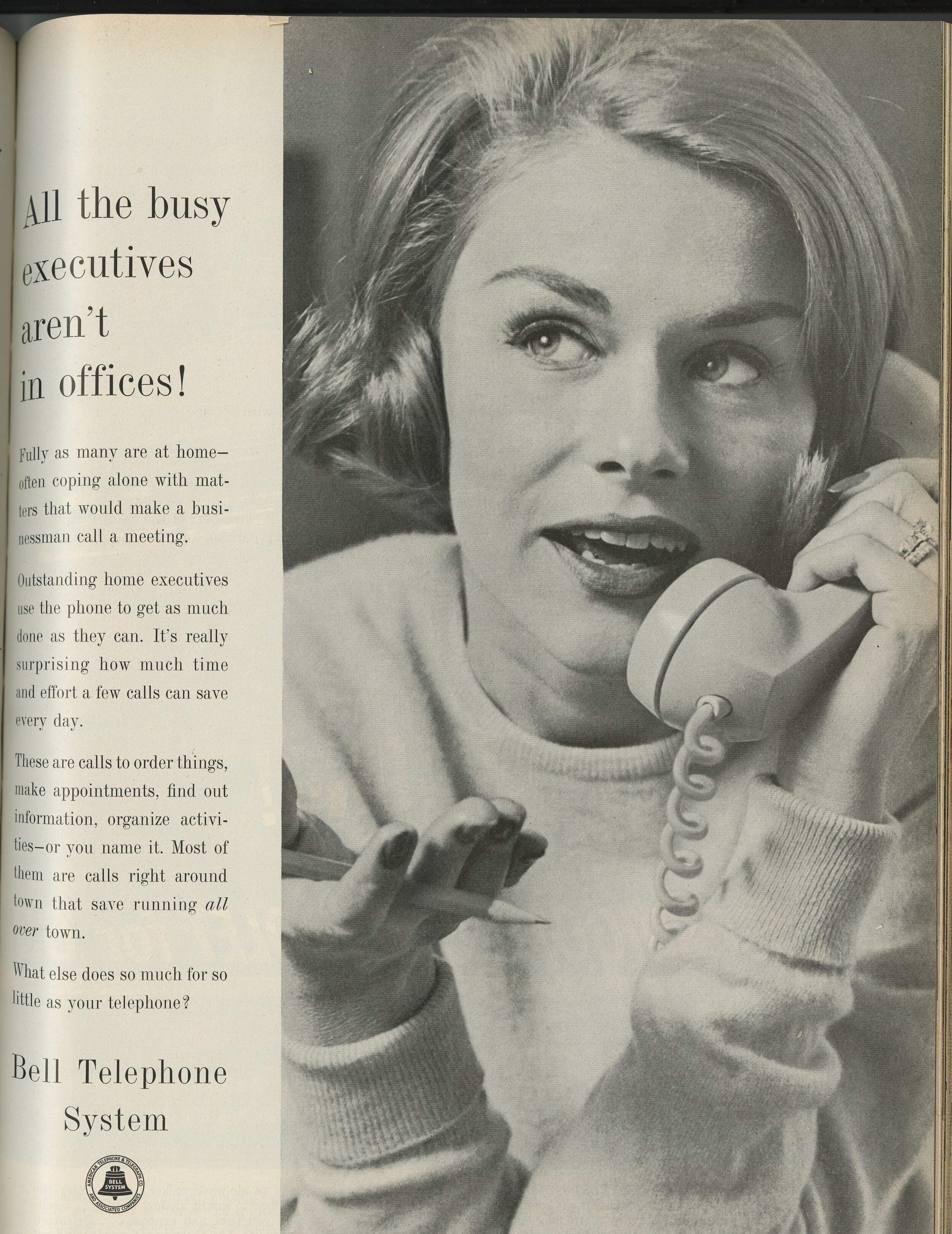

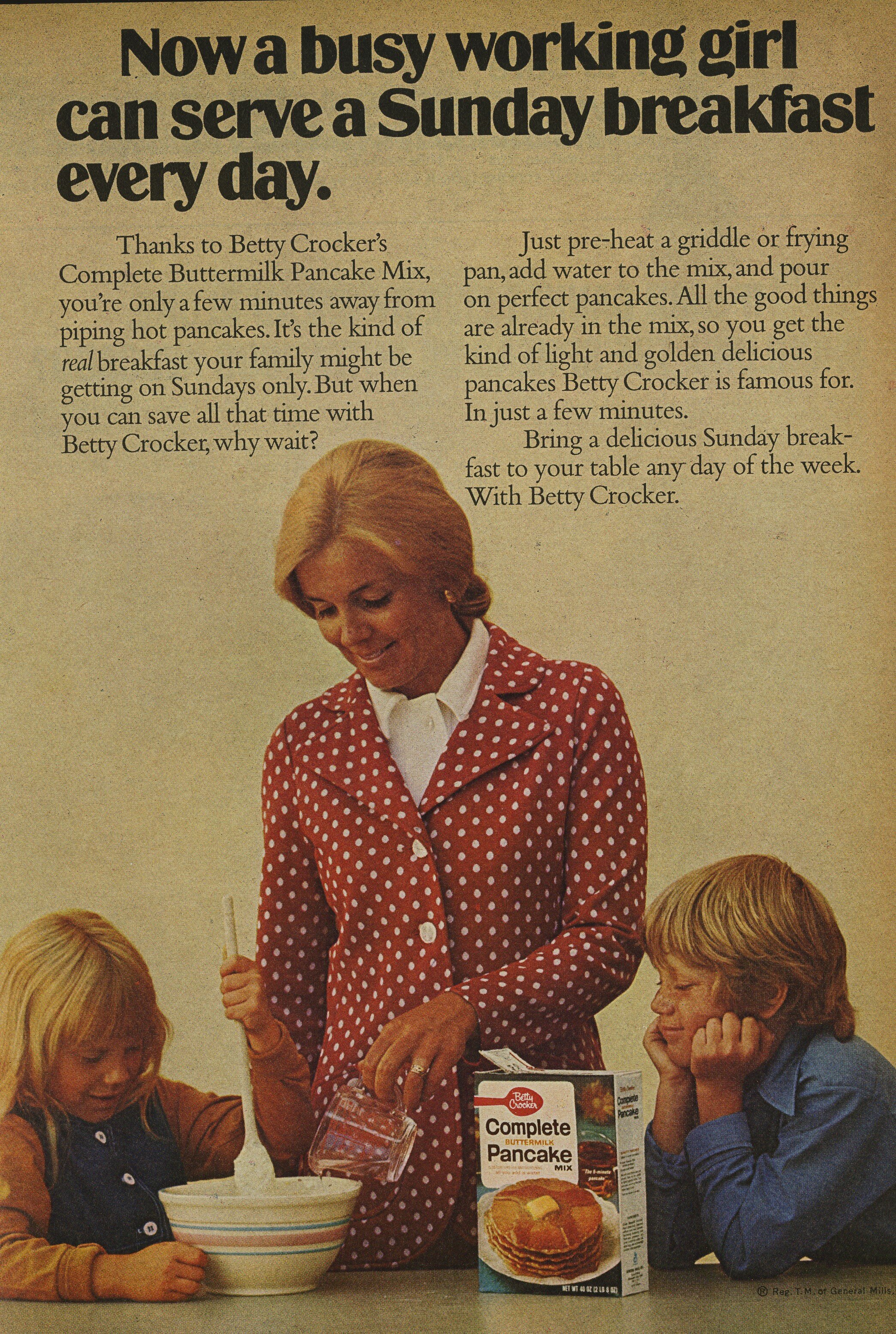

Or, for a guide on how to avoid such a fate, you can go into the stacks of the Prelinger Library in San Francisco and find volume upon volume of Better Homes and Gardens or Good Housekeeping. The collection there spans decades. Or, if you’re not in the Bay Area, you can just subscribe to either magazine yourself, as both are still alive and well.

In the pages of these so-called women’s magazines, I skip the articles and head right to the advertisements. Advertisements aren’t depiction of how we actually are. They’re utopic, in the etymological root of the word: they’re of “no place.”

In these advertisements, women — all young, pretty, and predominantly white — smile up from the pages. They bring out food to their families, or pose themselves against their house or with their appliances.

They are neat and trim, and therefore so are their houses.

This is the story we tell ourselves: that a woman is her house. She is the home maker. Her body is indistinct from the house she makes, and society waits in the wings to remind her where she is wanting.

Come play with us, Danny

It’s true that men often appear in the pages of home improvement magazines, or have entire periodicals dedicated to them with names like American Home... or American Builder. They tend to be full of tools and hands to hold them. In these instances there is also a greater frequency of language that labels men’s involvement in his house as a hobby, something notably absent from advertisements aimed at women. A hobby allows one to tinker and, perhaps most importantly, to fail. It exists separate from career-minded work, and so is detached from a capitalistic imperative to add value. In other words, it’s an area of play.

“Play” is often used to describe activities for children, as something that is outgrown, but play into adulthood allows us to view our capabilities and areas of growth as malleable. It’s kin to the more work-centric “skill building,” but “play” is inherently self-centered and self-directed. It’s not a requirement for your job; it’s for your own gratification.

I would argue that, for women, opportunities for play are often far less available, mostly due to how we are relationally attached to and conflated with our homes. Returning to the utopic fields of advertisement, women are often portrayed in work terms: as managers, executives, or economists of the home.

Even career women with families are assumed to be the main workers of the house, providing food, childcare, and housekeeping. How many hours she dedicates to a field outside the house is inconsequential to her duties within it.

If one is expected to work both outside and inside the home, there is little time left for leisure, that all-important requirement for play. And without play, a major avenue for self-exploration and self-redefinition is lost.

Ready, Player Two

To explore how women are expected and allowed to play, it’s helpful to look at something entirely dedicated to play: video games.

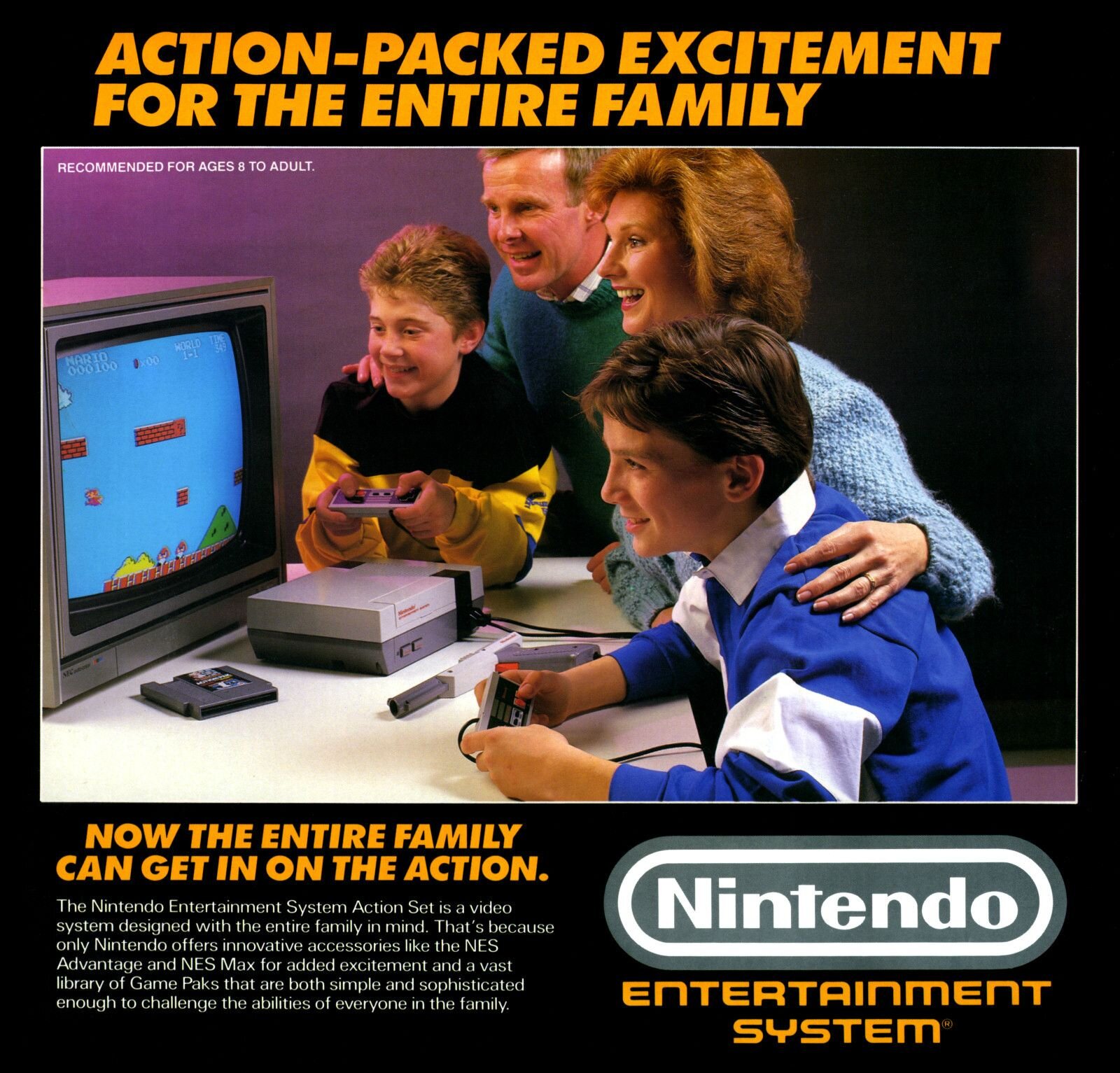

In Ready Player Two, author Shira Chess explores how video games are marketed to women. Early in the text, she includes an image for a game prototype from the 80s called the “Nintendo Knitting Machine” an add-on unit for the Nintendo Entertainment System, or “NES.”

I find this inclusion particularly on-the-nose because the NES as a console marked a major shift in who we thought of as video game players.

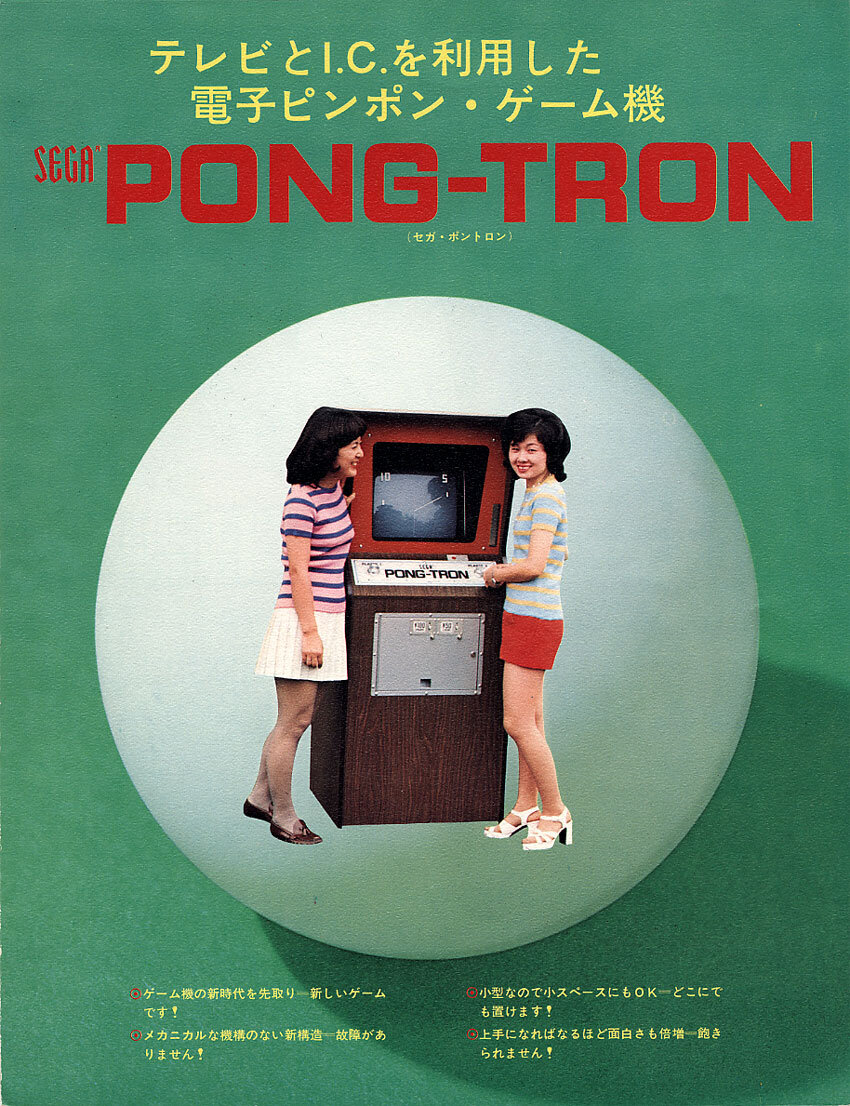

During the first video game boom in the 70s, led by Atari and its standout hit, Pong, advertisements for consoles were often broadly marketed, and usually promoted a communal aspect to gaming. A decade later, advertisements started to look very different. Specifically, images of girls as individual players started to disappear. There were a number of factors in this pivot, but two stand out:

First, in 1984, Reagan vetoed a bill that would have extended restrictions on advertising to children. With this veto, media producers could now market directly to children instead of those children’s parents. Kids were now a segmentable and targetable marketing group.

Second, the 80s marked a huge downturn in video game sales in North America. As Nintendo prepared to debut the NES, they conducted research to ensure their marketing efforts had the most traction possible in a bear market. They found that boys, just slightly, represented the larger part of their user base. So, Nintendo marketed to them.

So it became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Boys were targeted, so they bought games. Since boys bought games, they were targeted.

Let’s return to the knitting machine.

It didn’t even make it to shelves -- nor could Chess figure out exactly how it was intended to function -- but this was Nintendo’s pitch on how to market to girl gamers left behind. Or, perhaps, gamers isn’t the right word. In the copy for the knitting machine, Nintendo says it’s “Not a game; not a toy; not something a young girl can outgrow[.]”

If it’s not a game or a toy, what is it? Is it work? Perhaps not, but it’s certainly reminiscent of how we already expected girls to interact with play objects.

Throughout Ready Player Two, Chess asserts that the woman to whom these games are marketed doesn’t actually exist. Instead, this imaginary woman is the personified expectation of how women should interact with play objects.

So, despite the fact that there is a world of female video game players, as we’ve seen with ghost stories, Sarah Winchester, or -- more recently -- from the last election, facts have a hard time standing up against what we believe to be true or, even moreso, what is insinuated to be truth by virtue of its repetition.

Once more, in Simlish

I’ve heard a pejorative used to describe games marketed explicitly to women: “girly games.” In Ready Player Two, Chess lists a number of such titles. They have names like Cooking Mama, or Diner Dash, or Candy Crush, or Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, and they often feature core mechanics that look a lot like gendered work: time management, emotional support, cooking, shopping, and caregiving.

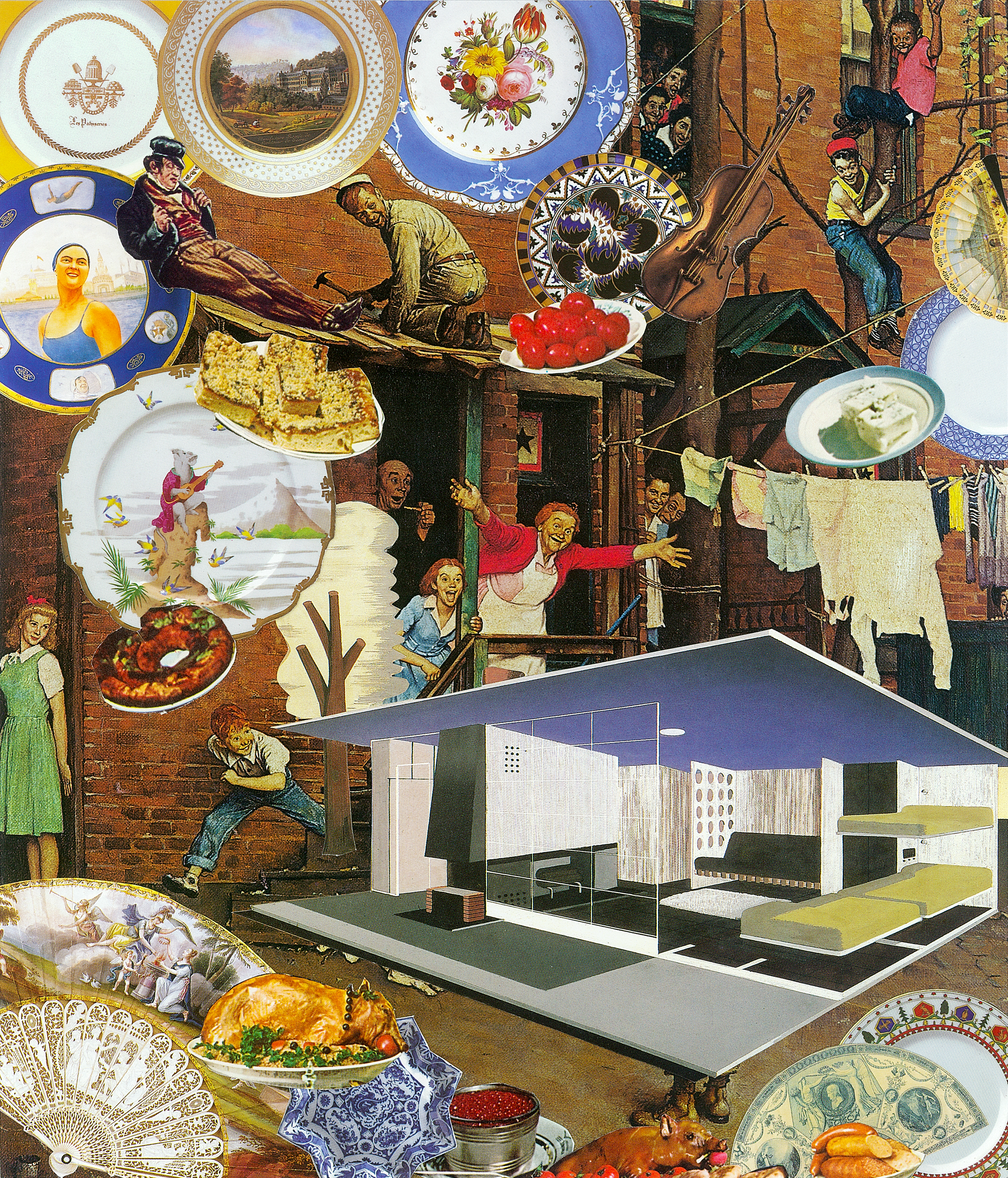

One game that combined all of these elements, with great success, is a video game from 2000, The Sims, in which players create digital humans, called “Sims,” and monitor the wide scope of their personal lives, from what their house looks like, to whom they marry, to how many kids they have, to reminding them to clean the bathroom. The game is open-ended, with no game over screen or stated final goal. It’s up to the player to determine the story of their Sims’ lives.

Like the Winchester Mystery House, The Sims is informed by the California landscape: The Sims’ lead developer, Will Wright, was inspired to create the game after his house burnt down in the 1991 Oakland Berkeley firestorm.

In a 2011 article for Berkeleyside, Wright described his mindset after seeing the ruins of his house, and assessing how to put his life back together. Having narrowly escaped the fast-moving fire with his family, Wright described wondering what he truly needed in order to materially rebuild his life, and what has been held on to for the pure virtue of having it:

“I started to wonder about all the things we have and how we purchased them for a reason. Why do we need x or y or z? Why do we think something will make me happier?”

Thus, The Sims was built around two competing ideologies: attaining happiness for one’s Sims by managing their needs like hunger, hygiene, fun, or sleep; and the only avenue for addressing those needs being the purchasing of household items to provide emotional boosts. It’s both materialistic and questioning of that materialism.

This also leads to an implicitly recommended task. You start the game with a player-created Sim, who has a limited income. Using this limited income, you have enough to build a starter house, with just the barest necessities. You are asked to allocate, or home economize. Do you choose to invest in an oven? Or do you get a microwave and use that extra money to buy a slightly nicer bed that will give your Sims more “comfort”?

Or, at least, that is how the game was intended to be played. In a 2006 interview with the New Yorker, Wright described using his daughter Cassidy as an early playtester:

“I never played with dolls, which is more of a social thing than playing with trains—it’s about the people in the house. Cassidy helped me see that. She and her friends got into the purely creative side of the game, rather than the goal-oriented side, which really influenced me a lot.”

The same article noted that 40% of Wright’s development team for The Sims was women, and that it received very little original support from its distributor since it was seen as a virtual dollhouse, and “dollhouses were for girls, and girls didn’t play video games.”

It was considered such a potential failure that when a demo for The Sims was brought to the giant video game trade show, E3, it wasn’t even included with the company’s other trailers on their main screen.

During that same E3, the developers presented a short, pre-programmed playthrough of a wedding in The Sims. However, they hadn’t had enough time to program all of their Sims, and it quickly went in an unexpected direction:

“On the first day of the show, the game’s producers [...] watched in disbelief as two of the female Sims attending the virtual wedding leaned in and began to passionately kiss. They had, during the live simulation, fallen in love. Moreover, they had chosen this moment to express their affection, in front of a live audience of assorted press. Following the kiss, talk of The Sims dominated E3. ”

The Sims team later joked that this kiss saved the project, and the game went on to be one of the first that allowed same-gender romance for playable characters. Though a developer was quoted as saying, “I guess straight guys that make sports games loved the idea of controlling two lesbians” what I remember is being a kid and playing The Sims with my friends, and the look in one of those friend’s eyes when two female Sims kissed on screen. We hadn’t planned it either, but her wide-eyed expression and whisper of, “I didn’t know they could do that”’ was enough for me to know it was important.

An online forum of one’s own

There’s non way to understate how well The Sims did financially.

The Sims 4 came out in 2014, and the franchise as a whole has sold nearly 200 million copies to date. It remains a money-making workhorse.

Though it was popular — is popular — the executives who expressed worry that the game was girly weren’t entirely wrong. The Sims today has a large, vibrant online community, one unlike any other I’ve seen, in that it’s largely and, more importantly, vocally occupied by women. Popular streamers like Lilsimsie, Ms Gryphie, LaurenzSide, Xureila, or Deligracy are all women, and all upload heaps of content a day for hundreds of thousands of viewers.

In fact, when I clicked on the one male face I saw among the most popular videos, it was for a Buzzfeed video titled “A Real Architect Builds A Mansion in The Sims 4.”

This women-led scene is not how most gaming spaces pan out, as evidenced most pointedly by GamerGate, in which groups of anonymized men on Twitter carried out coordinated harassment against female game developers, especially those who spoke up against misogyny in popular video games.

Certainly, there have been great strides in inclusivity over the past decade, sure, but look at any big name in online gaming, and it’s very unlikely that that person is a woman.

In my experience, that divide as a lot to do with perceptions of skill, and who has that skill. Competitive gaming is about technical ability: who can react quickest and respond fastest. Folks who do speed runs have to spend incredible amounts of time researching the best route or most exploitable glitches. Like the home hobbyists, these are activities that require time: time to play, time to fail, and time to improve.

So, there’s a divide: between the “real gamers” who play these technically difficult games, and “casual gamers,” who don’t. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that this, too, is a gendered divide. Assumed, and societally encouraged, to have little leisure time in which to achieve technical mastery, women are default members of the “casual gamer” category.

The Sims -- with its open-ended goal setting, lack of time requirement, and focus on aesthetics -- is perceived as a “casual game” and, therefore, belonging to women.

Gita Jackson, at the gaming website Kotaku, regularly writes a column about The Sims. In one she notes:

“Whenever I write about The Sims, I hear from readers that their wives are grateful for my articles. I don’t hear as much about those same people playing The Sims for themselves.”

At first glance, The Sims does look very much like a gamefied version of housekeeping, akin to the games mentioned by Shira Chess as ones that affirm jobs intended for women, rather than challenge them.

However, The Sims has built a franchise around the feedback that Wright received from his daughter, Cassidy: it has always prioritized player-first exploration and imagination.

When I play The Sims, I do so with nearly a hundred player-created modifications — or “mods” — that I downloaded from the internet. Most affect appearances in the game: new household items, or gender expression, or construction possibilities, or an increased range of Sims’ skin tones, or a cute new shirt. Others affect gameplay. My favorite changes the default mood for my Sims from “happy” to “fine,” making positive emotions feel more earned.

For some players, mods are a fun and easy way to customize gameplay, like a modder who made the Sims 4 urban neighborhood into a cyberpunk-influenced tech dystopia for deeper in-game roleplaying. For others, mods allow them to create more accurate versions of themselves.

In her book, Rise of the Video Game Zinesters: how freaks, normals, amateurs, artists, dreamers, dropouts, queers, housewives, and people like you are taking back an art form game developer anna anthropy comments on mod culture as an integral part of exploring video games:

“Hacks and modifications are made to subvert or comment on the original author’s intentions, or to simply correct what the modder feels is an oversight on the author’s part, or simply because it’s an easy existing infrastructure for creating something new.”

If mod culture grew out of a rise to see oneself reflected back, or to have opportunities for change and critique, The Sims embraced that fully from the start. Most games don’t make adding mods easy; the developers intended for the game to tell a certain story, and mods interfere with their designs. However, given how open-ended it is, The Sims has no such hang-ups. In fact, there’s an easy-to-access game folder to which players can copy downloaded mods, developer-written help guides on how to make sure your mods run smoothly, and an entire forum dedicated to sharing mods on the game’s official website.

And here’s where I find The Sims to be so quietly revolutionary. The malleability afforded by mods explicitly tells players that the developers don’t know, and don’t have, all of the rules. It’s not a paternalistic relationship, but a collaborative one, one in which storytelling can be developed and shared. Hidden behind a “casual gaming” veil, female players are given free access to a space where they can create what they desire to see, free of any authorial voice besides their own.

Let’s, For a moment, return to the winchester house

I invite you to take another look at the sprawl. Rather than seeing someone haunted by ghosts, see someone having fun, without having to worry about the consequences of being bad or making mistakes. See the rooms built in a myriad of styles, or the portions rebuilt until they were just right, or the elements that were built just for her own enjoyment. This isn’t a house for living in.

No, by virtue of her incredible wealth, disinterest in entertaining, and lack of any immediate family for which she had to be mother, wife, or home economist, Sarah Winchester’s San Jose house was a house for her to play in.

What would Sarah Winchester have been like as a Sims player? Might she have made something familiar? A Victorian style house, perhaps?

Or returned to something absurd within that familiar?

Or maybe she’d try some things like, truly off the beaten path?

We have told ourselves a story for a long time, that women are the houses that they keep, that the home is a place of work for women, without the opportunity for play or failure.

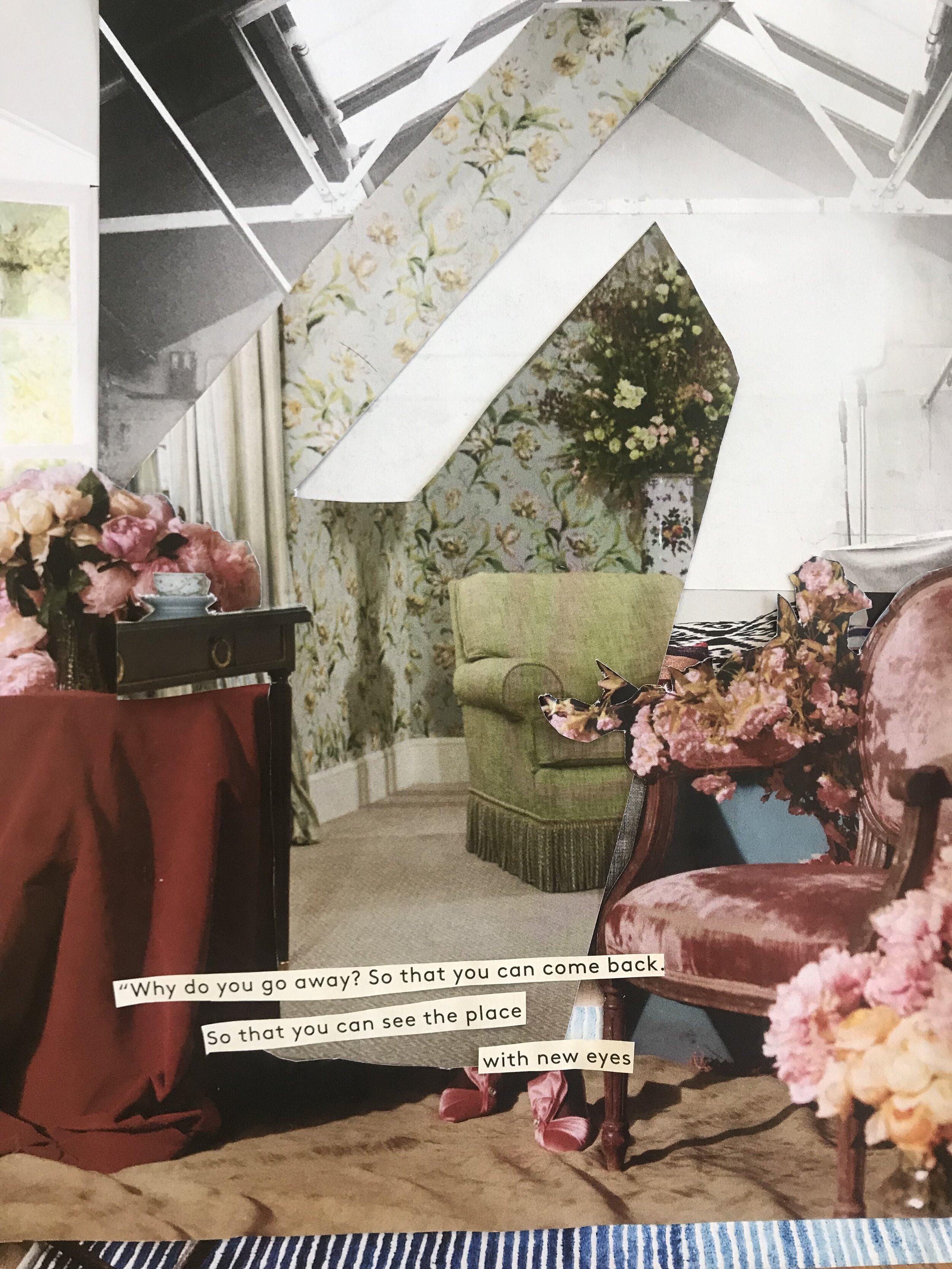

To counteract this story, it’s important that we recognize our own authorial, or architectural, voice. Taking the framework we’re given apart, beam by beam to construct something new. To become, as Ursula le Guin once said, “realists of a larger reality.” That we tell ourselves other stories. And not just one story. Story upon story upon story, closing off old hallways, removing the debris of what’s fallen, building things weird and wonderful and purposeful and utterly purposeless. This is where we see ourselves as who we are today, or how we might be tomorrow, or at our best, or at our ugliest, like a large, refracting mirror. Or a never-ending house. That is how we will view ourselves holistically, with love, and with the deep knowledge that the only ghost that haunts our house is us.