I love an end of year list. It’s so charming, to me, to see folks putting all their ducks in rows (look at those ducks! so lined up!) and ruminating over the Year That Was. Normally, I would join in the fray, with a list of gentler games that brought me joy.

But I’m not doing that this year.

It’s not because I found it hard to be as omnivorous as I usually try to be with games (though that certainly was true since my attention span in 2020 was, uh, a bit shot), but because, ultimately, the discussion can’t be without recognizing the reality we found ourselves in (alone, together) and how certain cultural touchstones resonated with a frequency that became louder by virtue of their setting.

To go with an obvious example: Animal Crossing: New Horizons would have been big any year, but it would its daily tasks have felt so very needed when we were grasping for any resemblance of productivity in the early spring? Would I have put up with Nintendo’s truly terrible online system to invite friends to my island so we could play our ocarinas at the digital shore? Would I have cried when it was my birthday and I woke up to find my villagers celebrating me, dancing bobble-headed around my in-game room on their little anthropomorphic feet? No, no, and no.

But Animal Crossing: New Horizons isn’t my game of the year. Nor is Hades, the game I enjoyed most and played in a fugue state, only later realizing how apt it was to play a game where I was trying to escape hell over and over again, only to be told There Is No Escape.

No, my game of the year is an episodic game whose final “act” came out in January of this year, before I had ever heard the term “shelter in place.” It’s a game that always felt prescient, concerned as it was with the great quaking storm of capitalism that’s always roiling overhead. It’s a game that I wouldn’t shut up about until the moment I finished playing the final act and found myself completely unable to talk about. It’s a game that, more than any other, shines brightest in this moment, serving both as an elegy and a hopeful clarion to some collective future.

Friends, it’s Kentucky Route Zero. It’s always been Kentucky Route Zero.

(Spoilers to follow, naturally.)

Kentucky Route Zero is, ostensibly, a point and click adventure game about trying to make a delivery.

At the very start of the game, Conway (an older man with an even older dog, and driver of the delivery van) pulls up to an unlit gas station, which is shaped like a giant horse head and is named Equus Oils. He’s looking for 5 Dogwood Drive, an address that can only be reached, he’s told, by taking the Zero, a highway that runs under the surface of the Kentucky soil in odd and confusing patterns. He needs to make this delivery; it’s the last one before his friend and employer, Lysette, closes up shop. She’s losing her memory. She’s also not there, though her ghost sure seems to be.

Lysette’s ghost is one of many encounter by Conway over the course of an evening:

There are the ghosts of drowned miners that appear in the flicking light of Elkhorn Mine, where Conway injures his leg in a tunnel collapse. Their shadows appear to be walking alongside Conway and his accidental companion (and daughter of two of the drowned miners), Shannon Márquez, moving out of the mine and into the moonlit entrance.

There’s Weaver Márquez, Shannon’s cousin, a woman who's there and who’s not, who tells him how to get on the Zero and mostly exists in television static.

There is the ghost of the town that used to exist. The player can drive around the above-ground Kentucky highways, reading descriptions of all the buildings that were closed and abandoned after being used by the Consolidated Power Co., the same faceless corporation that came in, bought the Elkhorn Mine, didn’t install quite enough safety measures to protect the miners, and have bled the town dry.

There is the storage facility that plays the recording of a church sermon, the congregants long gone but the rite still kept sacred.

There are the glittering undead skeletons who run the Hard Times Distillery, working there because they went into debt to Consolidated Power (who, of course, run the distillery) and this was the only way to pay it off. When Conway breaks his sobriety and takes a shot at the distillery, he learns that he, too, owes the company back. They thought he was there to work but, since he’s not, the celebratory drink is now actually at cost, and it was the Good Stuff.

Though Kentucky Route Zero is a narrative game based squarely in the court of magical realism, the metaphorical ghosts exist by nature of our literal American economic system, one that barrels down from on high, running on debt, and destroys what’s in its wake; a sort of capitalism that views everything and everyone as assets to be used; and one that flies out on gold-plated wings while yelling behind its receding silhouette to please forgive and forget, let bygones be bygones, even as we walk blinking back into the sun to survey its destruction and see what still stands.

And I’m not just leaping to conclusions with the whole “forgive and forget” aspect. Act IV of Kentucky Route Zero takes place along an underground river called The Echo. It’s a dark, subterranean space that people have moved to, constructing floating homes and drifting along. The river feeds into Lake Lethe, named after the underworld river of Greek myth that granted any drinkers pure forgetfulness. Along the Echo stands the Radvansky Center, a facility that tests peoples’ memories and is named after real-world researcher Gabriel Radvansky, who studied the phenomenon of why people forget things when they walk into another room. (Turns out, walking through doorways serves as a neurological reset cue for short term memory.)

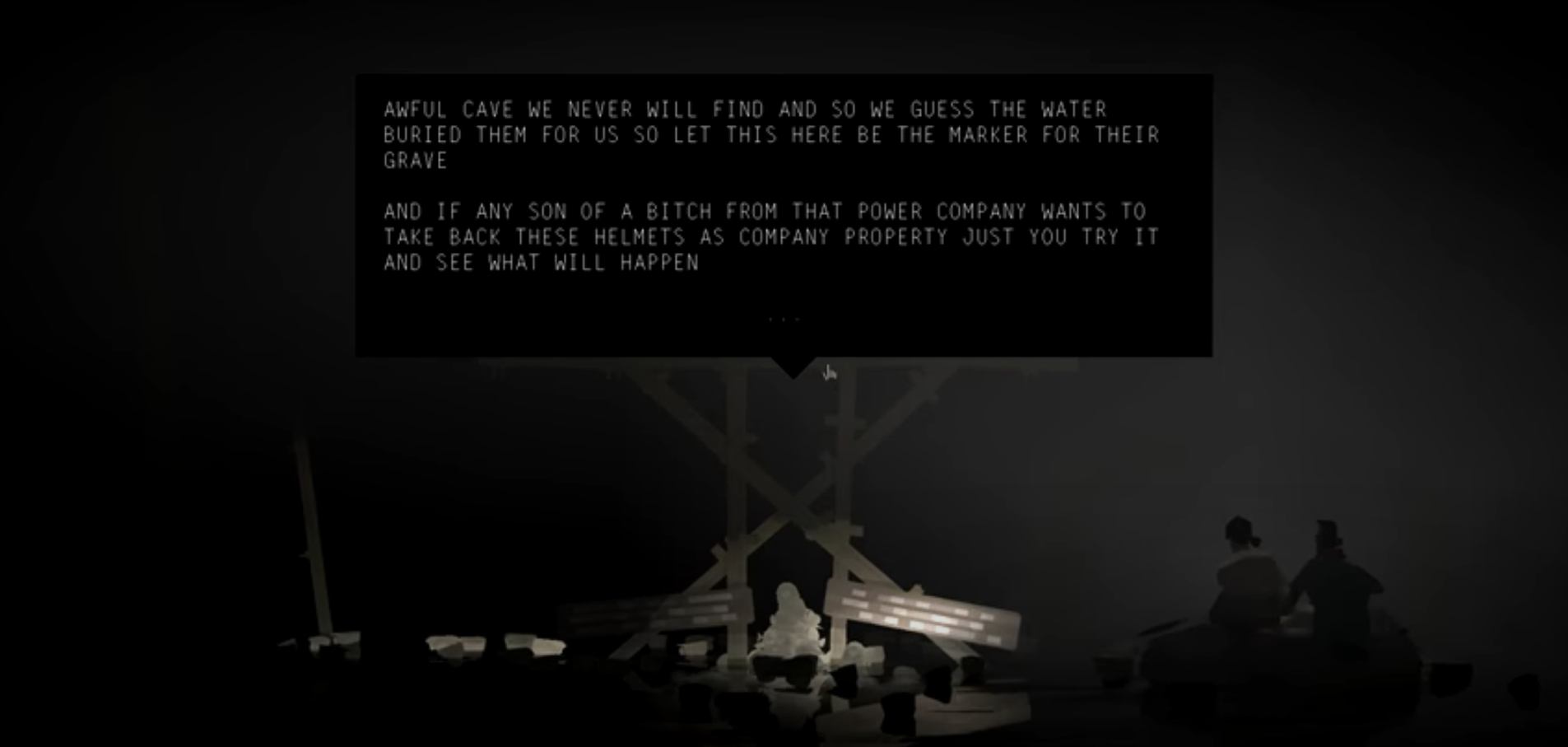

Also along the river is a memorial to the drowned Elkhorn miners. When Conway and Shannon boat come across the monument — a great wooden structure with hard hats floating under it — while making a mail run, the game displays the following text from the plaque, written in all caps:

WE CLAIM THESE HELMETS IN THE NAME OF THE FOLKS WHO WORE THEM AND WE PLACE THEM HERE IN THEIR MEMORY BUT ALSO AS A SPIT IN THE GREEDY GREEN EYE OF THAT POWER COMPANY WHO BOUGHT UP OUR OLD MIND AND TRADED OUR BROTHERS' AND SISTERS' SAFETY FOR A LITTLE MORE YIELD BUT ONLY YIELDED TWENTY-EIGHT GOOD MEN AND WOMEN DEAD WHEN THE WALLS COLLAPSED AND THE TUNNELS FILLED WITH WATER.

THEIR LUNGS WERE BLACK BUT NOW THEY'RE WASHED CLEAN AND FULL OF WATER TOO AND SWEPT THROUGH HIDDEN TUNNELS INTO SOME AWFUL CAVE WE NEVER WILL FIND AND SO WE GUESS THE WATER BURIED THEM FOR US SO LET THIS HERE BE THE MARKER FOR THEIR GRAVE

AND IF ANY SON OF A BITCH FROM THAT POWER COMPANY WANTS TO TAKE BACK THESE HELMETS AS COMPANY PROPERTY JUST YOU TRY IT AND SEE WHAT WILL HAPPEN

Conway says to Shannon, "Looks like it's been here a while. I sure as hell wouldn't mess with it.... you think whoever wrote it is still that angry?" Since the bulk of gameplay is through conversations, the player is given two options for how Shannon can respond, but both tell the same story: “I don't think you ever forget anger like that.” Or: “Sure, angry. Mainly just hurt.”

They boat on, and soon Conway is taken by the glistening skeletons from the Hard Times Distillery, there to bring him in to pay off what he owes. Conway’s human body evaporates, and he too becomes a glistening skeleton, as Shannon watches from the shore, unable to stop what’s happening.

If all this sounds dark and dire, it is. Especially (to crib language used by a billion marketing emails) after a year like this one, with so much pain, unduly distributed to those most at risk of hurt. Biking down the street and seeing buildings boarded up as the US government decides whether or not to be so kind as to give folks $2000 while deriding that they may use it to pay down their credit card debt, I feel the same storm from Kentucky Route Zero, ready to lay bare this little tract of earth we tried to make home, despite the odds.

And of course, through all this, I say that I am lucky, because I am lucky. I am safe, I am fine. But my community hurts, and yours probably does too. And this hurt isn’t new; it’s just been thrown into high relief. Like with crises before, we see with glistening clarity that forces outside of our control make decisions that continue to use humans like cogs to be worn down with time and use.

Sorry. I’m angry, have been angry, will continue to be angry. And I don’t think you ever forget an anger like that.

But Kentucky Route Zero isn’t my game of the year because it reflects this anger through the lens of magical realism Americana (or rather, this isn’t the only reason). It’s my game of the year because, among all that sad and angry, there are bright glistening moments of people just trying.

On his overnight journey — before he’s taken by the skeletons and Shannon must complete the journey herself — Conway comes across a number of people who have carved out something for themselves. There are the folks of WEVP-TV, a community television station that broadcasts out homemade documentaries and late-night poetry by middle-aged women and long phone calls about raccoons. There are the many musicians making music: a theremin player, a boy who takes field recordings on cassettes, a man playing an organ in a giant cavern. There are poets, and experimental electricians, and trouble-makers. There are two robots who used to be used to clean out the Elkhorn mines but who have fashioned themselves into humanoid forms, playing ethereal music that literally blows the roof off the joint, even if there are only four people there to listen, if you include the barkeep.

It’s a reminder: even in all this, people still live, and they find each other.

In the final act of Kentucky Route Zero, released in January, I expected some big explosion, some divine reckoning for Those Who Have Hurt People. I wanted to tear down Consolidated Power Co. and save Conway. But that’s not what I got. Kentucky Route Zero doesn’t pretend that these few are going to change the crush and the roil of our current state of late capitalism. They aren’t the antidote or some white knight that’s going to rush in and slay the beast. The TV station is washed away by the storm. Folks aren’t sure if they want to make music anymore. Conway disappears. People are lost.

But, in Act V, I do make it to 5 Dogwood Drive, in the end. Most everyone does. They all step out into the light and survey the destruction to see what still stands. They drag away the refuse and salvage what’s still usable into a new home where no roads can reach them. They mourn what they lost. And then they play music, again.

For the past few months, in the early morning or at dusk, a vision crosses my mind. It’s a vision that, when I try to focus on it too hard, brings a pain to my heart so strong that it knocks the wind out of me for a moment.

I imagine a collection of houses in the woods— small houses, nothing fancy, made of wood and full of cozy yellow lights. I imagine these small houses circling a center square with other small wooden outhouses: a kitchen, a stage, a greenhouse. I imagine my friends and family and me living in these houses. I imagine us all having lives there, caring for one another, making things that bring us delight, cooking together, getting into fights, learning to live together, and moving forward in collective warmth.

It’s the same utopic vision, I’m sure, that spurred on Back to the Land folks in the 1970s, those doomed hippies who wanted to shun the life that capitalism laid out for them, but who found farming and homesteading to not be the promised solution after all. Even with this knowledge, I want it so badly.

And though I might not literally have a group of houses in the woods, in the moments when I’m writing with friends, or working on weird little art projects, or making my mom and dad laugh on the phone with a dumb joke, or seeing my partner quilt, or cooking a soup, or hearing my friends sing a beautiful song…

I’m there.