I flew into the sun. I flew into the sun again. I landed on a planet and got sucked up into a geyser. I flew into the sun a third time. I landed on a planet, fell through the crust, and landed in the black hole at that planet’s core, which ejected me into a far reaches of my solar system, which led me to asphyxiate in space when my oxygen ran out. I flew into the sun a fourth time.

I then somehow avoided running into the sun and instead puttered my way to another planet (one with actual soil and no geysers). I managed to safely land my ship on a short bridgeway, mostly by accident. I left my ship and followed a passage inside, one that was slowly but surely filling with sand. I saw a light in the distance, and was curious. I managed to find some bits of text etched on the floor. Reading it updated information in my ship’s log. Then, as I went to explore another room, my solar system’s sun went supernova and everything turned bright white. It wasn’t unexpected; it did this every 22 minutes when I didn’t otherwise die by geysers or the vastness airlessness of space or by flying into that same sun.

Then — as I did every single time I died — I woke up, again, at the base of my spaceship’s tower before my “first launch day,” because I was in a time loop only my character seemed to know existed.

I got back in my ship and reviewed the new information in my ships’ log (which saved, even though it was a time loop ago). I made a plan on where to go next, buckled in, took off, and promptly flew into the sun for a fifth time.

The sun is very big, turns out, and so bright, and so easy to fly into.

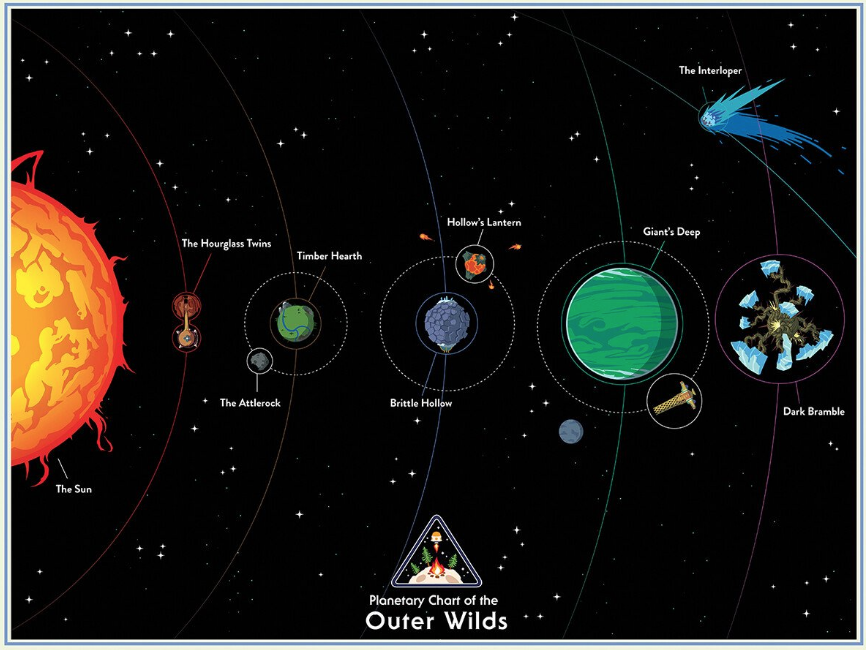

Outer Wilds is an exploration and puzzle game (and is not to be confused with Outer Worlds, the Bethesda-like that came out around the same time). You play as a Hearthian, a creature that, by our human standards, is an “alien.” Hearthians have humanoid proportions, blue skin, and four eyes. They make their home on the planet of Timber Hearth. They have cozy wooden homes, a gorgeous museum/observatory, a tight-knit community, a love for bluegrass-inspired music, and a recently-developed space program.

The player, as you may have gathered, plays one member of this new space team. Other members of the team are already exploring other planets. One is lost in space. The player is the first of this nascent space team to be equipped with a translator tool, used to decipher messages left around the solar system by the Nomai, another race that mysteriously disappeared before the Hearthians came to be.

And there you are. You: charged with exploring, with absolutely no knowledge about what you’re supposed to be doing, besides “go to space.”

But go forth to where? The first time I launched the ship into space, I found myself drifting among the stars, looking at the other plants in the system, unsure where to go. It was counter to my usual lodestar in video games: normally, there’s a quest guide, or an NPC leaning against a tavern wall, or literally a big arrow painted on a wall (I’m looking at you, Portal 2).

But here? Here there was just vast inky blackness and a few planetary dots. And a big ol’ sun I couldn’t seem to not run into.

When I reread the above, it’s painfully obvious why Outer Wilds can be a difficult game to get into.

In fact, I picked it up months ago, after reading the accolades upon accolades it received: Polygon included it on their “Best Games of the Decade,” list; Jason Schreier at Kotaku called it “a tremendous experience;” and Jay Castello at Rock Paper Shotgun said, simply, it’s “an incredible game.”

All of these reviews also follow up with a caveat, along the lines of: “Stop reading this now. It’s best to go into this game completely unspoiled.”

And, being a good rule-follower, I didn’t read those reviews. Instead, I played Outer Wilds and kept dying, over and over. I started to uncover some mysteries in the game, but they were small scraps, and I had trouble seeing how things were supposed to connect. I like being good at things, and I wasn’t good at this. (See: my many trips into the sun.) I got frustrated, and I felt like I was doing something wrong.

But, this past week, I felt something in my gut that said, “feeling like I was doing something wrong might be part of the point.” When I opened the game back up, I went in with that feeling, and it re-oriented my entire experience.

I’m now knee-deep (slowly approaching neck-deep), wading through Outer Wilds' surprising vastness.

This is why I’m writing this mini-review now. Not only am I pretty incapable of (and uninterested in) spoiling the game’s plot at this point, but I want to sell this to you based on the feeling I’m in now: one of curiosity and surprise, and the complete lack of knowing (and joy in not knowing) what’s coming next. In other words: it perfectly captures the many myriad feelings that swirl around discovery.

You know, it’s a little like reading Ursula Le Guin.

In case you haven’t read her work before, Le Guin was a science fiction writer, though she bristled a little bit from the title, given that any genre writers are typically segregated from “real” fiction writers who write about “real” things.

And Le Guin’s books are certainly science fiction. There are non-human characters from other planets, and galactic alliances, and warp engines. But Le Guin wasn’t exactly interested in writing page-turning space operas. Instead, she leaned heavily on the “science” part of science fiction, and her books feel more like narrative explorations of social hypotheses. In other words, le Guin would pose a question to herself, and then write a novel to explore a possible answer.

There’s The Dispossessed, which is about a moon inhabited by a radical communist sect, who (among other things) have created a new language for themselves that doesn’t include possessive pronouns; after all, why would you need to say “This is mine” or “This is hers” if everything truly belongs to everyone?

There’s The Left Hand of Darkness, which features a civilization of humanoid aliens who all are equally able to bear and sire children, making reproduction-based gender discrimination completely moot. Le Guin is then able to explore what sorts of societal hierarchies develop (or fade away) when gender is a non-factor.

I have trouble recommending le Guin’s books to people because it feels like I’m asking them to read a scientific text. It feels a little like homework. But, I promise, if you stick with it, you realize that this difficulty is in part due to the fact that her novels aren’t meant to distract you from the “real world." They’re not escapist fantasies, but intend to draw one’s lived reality into hyperfocus in order to better understand it and to critique it.

When Le Guin was awarded the lifetime achievement award from the National Book Award in 2014, her acceptance speech reveals this intent:

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art - the art of words.”

She calls her fellow science fiction and genre writers “realists of a larger reality.” This is reflected in her writing. Her books explore a vast, but deeply personal unknown. When one is inundated in the day to day realities of being alive, it can be hard to step back and see the many chains and social machinations that keep one in place. Reading a book that takes a central aspect to one’s experience — gender, economics, class — and picks it apart with questions and narrative possibilities becomes, ultimately, intensely freeing. It changes “here is how things are” to “here is how things are right now.”

It’s a temporal shift, one that feels all the more possible when framed by storytelling. Give me Didion’s we tell ourselves stories in order to live, and I’ll raise you Le Guin’s implied we tell ourselves stories in order to imagine.

More than any other game I’ve played — more than Myst, or The Witness, or any other exploration/puzzle game Outer Wilds has been compared to — Outer Wilds feels like it has truly taken to heart Le Guin’s missive for imagination and exploration so as to better understand oneself.

In this way, it rives at the core of what science fiction can offer. Free from the gravity of “reality,” one can drift through possibilities, find oneself in parallel existences are are so close (yet not quite) one’s own experience, or just drift among the starts for a while.

If we were to put a Le Guin-type social hypothesis on Outer Wilds it might be “What if all the danger in exploration were removed?” Outer Wilds shows a solar system full of fatal peril: geysers and black holes and asphyxiation and flying into the gosh darn sun again and again. But you always wake up, anew, again, still retaining all the knowledge you’d gleaned before you died the last time.

Surely, this isn’t the first game to remove death from the equation; there are very few games that have permadeath (wherein when you die, the game is over and you have to restart everything). However, it’s one of the few I’ve played that recognizes death as part of the equation of life, draws focus to it, and then removes its final sting.

What would you do when you knew nothing, but had the possibility to do anything? Would you, like me, still feel the vestigial fear and panic when you found yourself in a dangerous situation? Would you, like me, feel that fear, and then wonder why you needed to feel that fear at all, given that you were going to die, no matter what, so why not explore?

Would you, like me, step back and wonder since (truly) we’re all going to die one day anyway, why not go out there, explore what you want to explore, make the world you want to make, become the realist of your own larger reality?

Outer Wilds is a beautiful game for many reasons: it has a gorgeous soundtrack full of banjo and harmonica and also swooping orchestrations; the level of detail to each individual planet, creature, and item reveals a deep and complex backstory that only gets more touching as new bits of information are revealed; it has smart puzzles that make you feel like a genius when you figure them out, whether through careful planning or dumb luck. Though Le Guin isn’t always a page-turner, Outer Wilds is. I keep getting scraps of information, and I find myself hungry for more.

To be honest, I have cheated a little. I get anxious and look up answers because I have a deep fear of doing things wrong, or of not being smart enough to figure it out. I regret doing that, but, then again, I’ve always been an over-preparer. I am a scholarly explorer(, I tell myself, quietly).

But Outer Wilds is encouraging me to try another route because, more than anything, it’s an incredible love letter to the wonders of exploration in all of its difficulty and terror and frustration. Beyond the vertiginous feeling of being given no instructions, one comes to realize that you only needed the one instruction it did give: Go forth.