In elementary school, my friend and I had a brief stint of popularity when we advertised ourselves as being able to see and communicate with ghosts. One or another of us had received a Ouija board, and we spent long afternoons squealing accusations of "YOU'RE MOVING THE BOARD" and/or "NO, YOU'RE MOVING THE BOARD!" We had a regular "spirit" correspondent (Alice? George?), who would field our questions about our present lives and possible futures.

I don't remember how it got to this point, but someone at school overheard us talking about our after-curricular activities, and we eventually asserted that we could talk to ghosts. Classmates would huddle around us during recess, asking us to relay quotidian questions to our ghost friend.

In my heart, I knew what we were doing was fake, and I'm sure our classmates did too, to some extent. But we were at a point in our young lives where we were surrounded by so much information. Being in school meant that we spent every day confronting new realities about the physical and intangible world. We were learning that the oceans were full of more creatures than we thought, that numbers could be manipulated into complex equations, that the land we lived on had a long history that was older than our parents, their parents, or their parents' parents. In short, we were learning that there was more to the world than we could imagine. So, two girls asserting that they could talk to ghosts was just another drop in the giant bucket of possibilities.

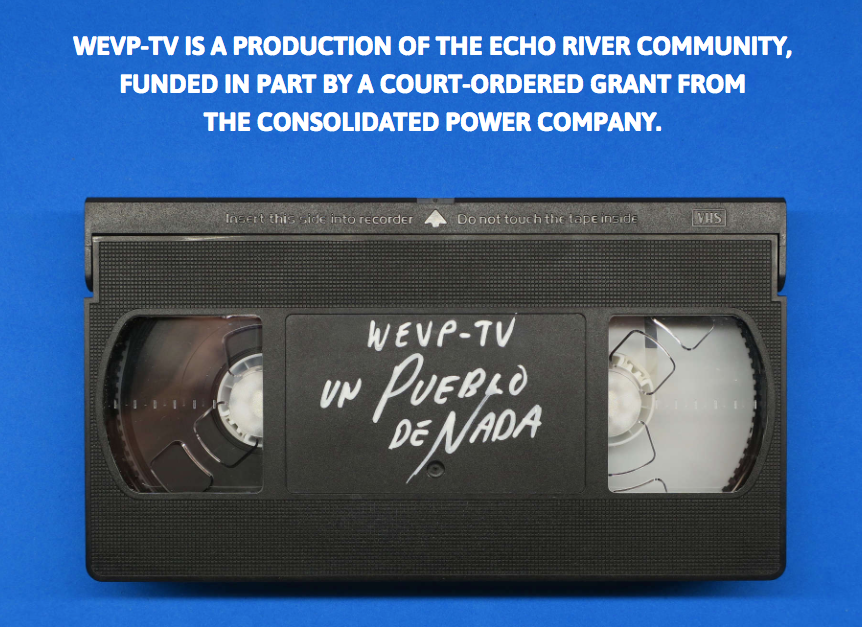

Kentucky Route Zero is a game about ghost stories. Or, rather, it's a game about being haunted. It's also a game that I evangelize to literally everyone, even though it's not even fully completed. Rather, its developer, Cardboard Computer, has released four of its five promised "acts." It's often over a year between one act and the other, and Cardboard Computer soften the blow of having to wait by releasing short interstitial games in between each act. Once, they wrote a play. Another time, they created an elaborate and labyrinthian phone tree. This time, they've maintained a website that is representative of the in-game public access television network, WEVP.

For the past year, wevp.tv has hosted a number of shorts, all of which either were or had the feel of home-made analog tapes, like the kind you'd see on a late-night local television show. Some had connections to pirate television stations, or to famous acts of pranksters jamming local television channels (like the Max Headroom incident of 1987).

However, this past month, Cardboard Computer put out word that there was something special at wevp.tv. Anyone who went over found footage of a woman in a public access-style set-up, talking about characters and locations within the Kentucky Route Zero world. It features guests, showcases of tapes, an avant-garde weather forecast, and (my personal favorite) a call-in viewer with a long drone about watching raccoons. It also, true to Cardboard Computer standards, has a phone line where one can call in to leave messages. The broadcast ends with an interruption. Within the narrative of the game, there's a looming presence of a character named Weaver, a cousin to one of the playable characters. Weaver is most known by the citizens of the game world because she would show up on WEVP transmissions in disconcerting ways. At the end of the video, the "broadcast" cuts to static and a low drone. Suddenly, there's Weaver.

Cardboard Computer also released a companion game called Un Pueblo de Nada, which shows a behind-the-scenes view of the taping, with the player controlling Emily, WEVP's producer. It's Cardboard Computer's most refined offering to date. (The fact that they release the acts so infrequently means that each is more technologically complex than the last.) It's beautiful aesthetically, with an expert eye to creating a stage picture. Thunder booms outside. When Emily is lost in thought, large white illustrations spiral around whatever she's looking at. The puddles on the floor turn from small points of refraction to giant pools of light.

In the game, Emily observes two characters fiddling with a radio, talking about the static in between stations, and the phantom voices you can find there. Later, she watches helplessly as Weaver overtakes the airwaves again, a ghost in their machine. Then, the station is destroyed by the storm that has raged outside during the entire broadcast, taking the people inside with it.

Like I said: Kentucky Route Zero is a game about ghost stories. And it's the first game I've played that recognizes the mystery in the medium it inhabits, and reveals our hauntings as something of our own creation.

I remember a book that I had on my bedroom shelf around the time of my brief stint as a schoolyard medium: The Way Things Work. In it, a cartoon mammoth explained the inner workings of objects in our modern life. It connected simple mechanics to items like televisions and washing machines in an effort to de-mystify the inner workings of these items. (The book has apparently since been updated for the digital era.) As a child, even with this book, the items it described still felt a little magical. Sure, The Way Things Work showed me what the insides of a television looked like, but it didn't describe everything. And so what it didn't describe must be a miracle.

It's no wonder that the American Spiritualist movement of the 19th century (which happened to coincide with the tail-end of the industrial revolution) utilized newer technology of the time to fill their stories with ghosts. Spirit photography and spirit trumpets (large horns, like that of a phonograph, said to magnify the voices of ghosts) were both utilized by mediums to convince others that ghosts were present. This trend continued as technology advanced: people look for ghosts in radio and television static; Ringu/The Ring played with the idea of haunted VHS tapes; and Twitter user Adam Ellis has been exploring what a ghost story via Twitter looks like with his Dear David thread.

Kentucky Route Zero examines our reverence and anxiety around items that increasingly fill our homes and lives. We're surrounded by little boxes that, no matter how many times we ask "Remind me how this works?" we still never completely seem to understand. We think of radio, television, and internet signals passing through the air (or through us) and it seems natural to wonder about what these signals pick up on their way from point A to point B. It's like being in elementary school again: overloaded with information and knowing that we're surrounded by so much that we don't understand.

Look at the machines that we've built to accompany us. Look at us filling the gaps in our knowledge with possibilities, myths, and spirits.